Why more megapixels on your phone camera isn't always a good thing (but sometimes it is)

Anyone paying attention to smartphone specs in recent years may have noticed manufacturers upstaging each other by increasing the megapixel count on their devices. Bigger numbers, bigger sensors and bigger expectations, but all isn't as it seems once you dig deeper.

It harkens back to when digital point-and-shoot cameras were measured the same way in the 2000s, though it was largely a mythical marketing ploy. Phones have since replaced those compact cameras, yet history is repeating itself again in the smartphone arena. Only this time, there are far more nuances at work.

Hosted by Android Central's Alex Dobie

Join us for a deep dive into everything you need to know to take better photos. Composition, software features, and editing are just some of the features we'll be tackling together in this course.

Measuring megapixels

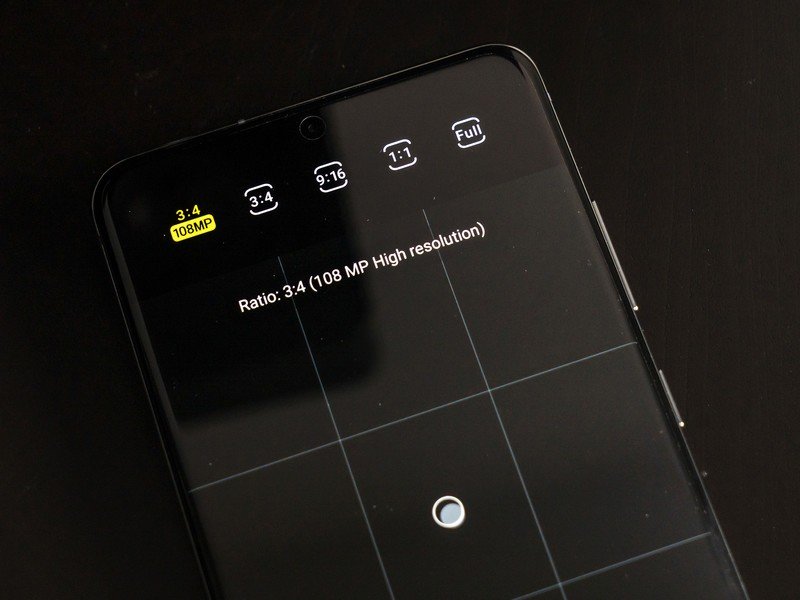

Let's put some perspective on this first. Images are made up of dots of visual information called pixels that number in the millions. Hence, megapixels. Unlike video formats in the HD era that are in 16:9 aspect ratio, most photos come out in 3:2 or 4:3 (though you can shoot in 16:9, too). That can skew how pixels line up, which can seem confusing if you're comparing still photos to video, but the point is that the higher the count, the better an image looks on a 4K or 8K TV, and the easier it is to print.

It may seem logical that more megapixels would lead to better photos, but that's not always true.

It might seem, at least on paper, that larger megapixel counts on phones would lead to better photos — or at least greater flexibility when shooting. The problem is these smaller sensors on phone cameras are squeezing pixels more tightly together, which can have consequences. First, there is a higher likelihood of noise creeping into the shot at higher ISO, and second, it adversely affects low-light shooting because smaller pixels mean less light hits the sensor in the first place.

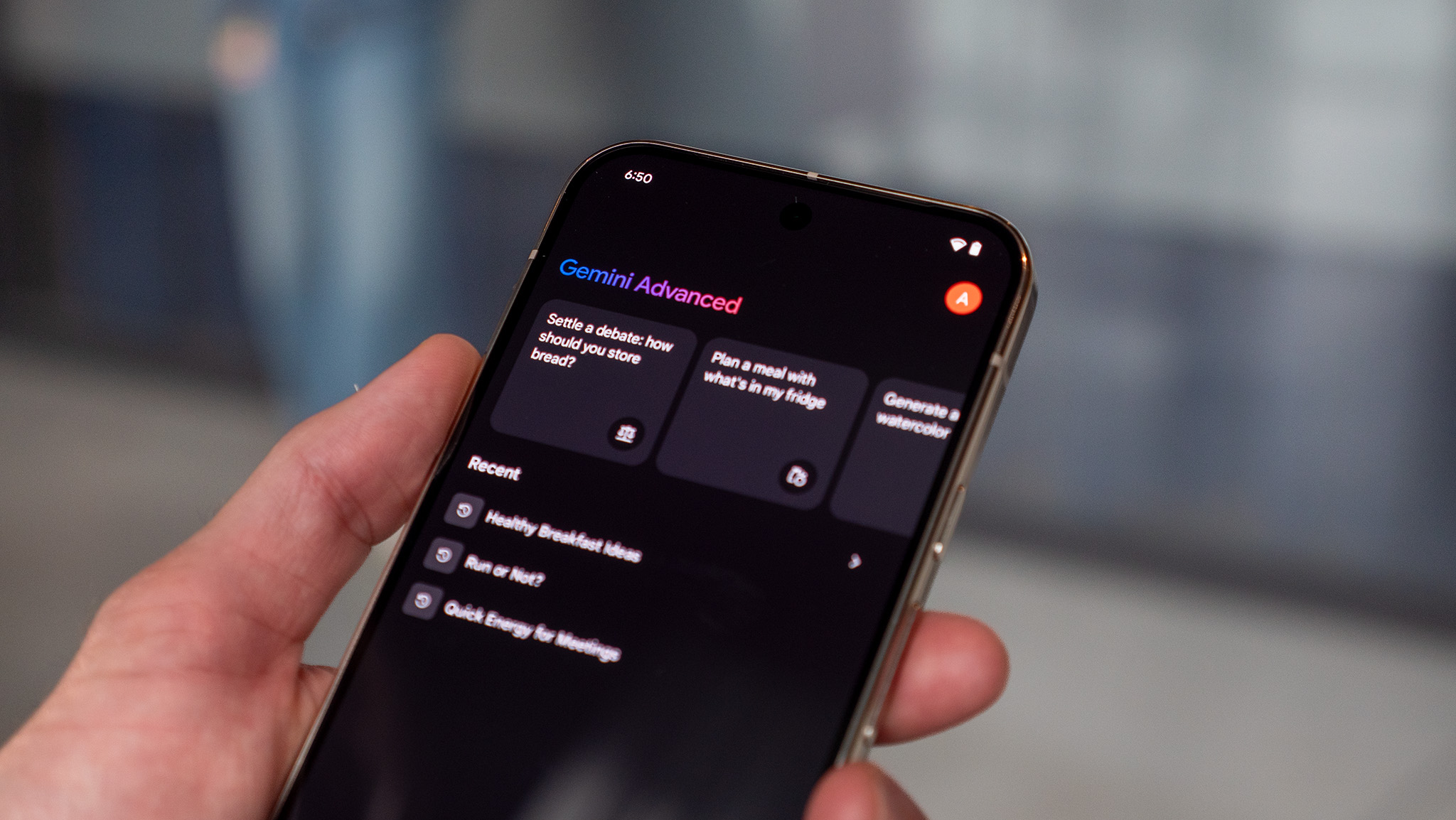

Samsung highly touted its 108MP sensor in the Galaxy S20 Ultra for producing images so detailed that you could crop out almost anything out of them. In reality, it's actually a 12MP sensor that uses pixel binning to split each pixel by a factor of 9:1 to reach 108, so it's really software doing the work.

Shooting at that resolution is elective, and for good reason, because the standard 12MP wide camera shoots better in low-light than the 108MP mode does. How? The pixels are larger, thereby taking in more light. There's also less noise at higher ISO levels. It's the same reason why the phone's Night mode shoots at 12MP and not 108MP. Technically, more detail would come in at the higher number, but software would also have to work harder to drown out noise and pull in more light simultaneously.

It's about the sensor

The sensor is the key to how well a phone's camera will perform. The speed and quality of the lens is also a major factor, but since these devices are constrained by physical space and optics, the sensor and software supporting it play integral roles.

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Samsung's primary sensor in the Galaxy S20 Ultra measures 9.5mm x 7.3mm. In phone terms, that's monstrous compared to the competition. Even the iPhone 11 Pro Max, using a 7.01mm x 5.79mm size Sony Exmor sensor at 12MP, is small by comparison. To be fair, the Google Pixel 4 and Pixel 4 XL are also using the same size sensor. As does the Huawei P30 Pro, which uses a Sony Exmor sensor as well.

A large sensor is usually more important than a phone with the highest number of megapixels.

This is arguably the biggest reason why phones will be struggling to match DSLRs or mirrorless cameras for a long while. A full-frame sensor on one of those cameras, which is the equivalent of 35mm film, is 36mm x 24mm. Smaller APS-C sensors on some mirrorless cameras are 22.2mm x 14.8mm, so still a considerable size difference.

And so, software has to step in and pick up the slack. Google and Huawei have each staked their claims to being the best in the business because of how their respective software interpolations work. It also shows that Sony, a major supplier of CMOS image sensors for various phone brands, can play such an impactful role in smartphone photography, yet never seem to get it right on its own handsets. That's the power of software.

When megapixels come in handy

Samsung was correct about one thing when it first unveiled the 108MP camera: it can make it easier to shoot from a distance. The company's terrible 100x Space Zoom, notwithstanding, shooting at 108MP in daylight conditions can deliver a photo good enough to crop.

It's the main reason why the 3x zoom on the Galaxy S20 Plus and Galaxy S20 is a mirage. The optical portion of that zoom is only 1.06x, whereas the rest is simply cropping the outer edges to "zoom" closer. Samsung pulls that off on those devices by using a larger megapixel count on the telephoto lens. It's also the same reason those phones use that lens to record 8K video.

OnePlus essentially did the same thing with the 7 Pro, which advertises a 3x zoom, but is actually 2.2x optically, with the rest being a crop factor. For the most part, a 48-megapixel image can manage the equivalent of a 2x optical zoom without degradation. Any more than that, however, and software will have to step in and try to clean up any messes.

This is partly why hybrid zooms have been getting better. The 10x hybrid zoom on the Galaxy S20 Ultra is quite good in ideal lighting, but the primary reason why it's superior to the other two S20 models is because it has true 4x optical zoom in the telephoto lens. The software doesn't have to pull as much weight to make up the difference and get the same shot.

More megapixels on a phone isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it's not the metric with which we should measure prospective performance. The image sensors and supporting software are doing the real work, and that's where the real innovations will be moving forward.

Ted Kritsonis loves taking photos when the opportunity arises, be it on a camera or smartphone. Beyond sports and world history, you can find him tinkering with gadgets or enjoying a cigar. Often times, that will be with a pair of headphones or earbuds playing tunes. When he's not testing something, he's working on the next episode of his podcast, Tednologic.