VR isn't accessible enough. How can the medium's platform holders fix that?

Recent years have seen accessibility become something of a hot-button issue in game development. Games like The Last of Us Part 2 and devices like the Xbox Adaptive Controller catapult the discussion around accessibility to the forefront of the gaming landscape. Stories of disabled gamers from around the world getting to interact with games in new ways, some for the first time ever, have become more and more common.

To accessibility consultant and developer Brian Van Buren, however, that rising tide hasn't quite lifted every ship. "Often, when people have disabilities in their lives, they have various different sorts of adaptive technologies to allow them to interface with various things, but I don't feel like VR developers have quite come to terms with that yet."

What's wrong with VR right now?

VR development faces a number of challenges when working to make another reality more accessible, not the least of which being that neither Facebook nor Valve, the largest platform holders for VR, promote the solutions that developers find.

Alexis Miller, Director of Product Management at Schell Games, the developer behind the I Expect You to Die series on VR headsets, knows this problem well. "Even if developers put a lot of effort into making these features, it is incredibly difficult for the players to know that they're there," she said.

One of the biggest barriers disabled players face in VR starts before they even sit down to play a game.

One of the biggest barriers disabled players face in VR starts before they even sit down to play a game. "You can't go to the store page on Steam or on Quest and search for an accessibility requirement," Miller added, which means that disabled players might buy a game that isn't accessible to them without realizing it. "That's not a very consumer-friendly system."

Van Buren believes that Facebook owning Oculus is the source of a lot of the platform's problems. He said, "Facebook has a very different set of parameters on what they want their company to be and what their company should do" in comparison to a number of other players in the game industry.

He added, "I don't know that having a VR headset or a platform on top of that really makes sense to them or fits into their company's goals." He went on to surmise that Facebook probably wants to use VR for its ethereal Metaverse, a concept that even Facebook doesn't always seem to have a firm grasp on. "They're looking for the simplest path to get there," he added, "Accessibility isn't always the simplest path to get there."

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Not two weeks after he said that, Facebook seemingly proved Van Buren right.

On Sept. 27, Facebook published a news release, titled, Building the Metaverse Responsibly, a $50 million investment into a number of organizations to help ensure "equal economic opportunities, privacy, safety and integrity, and equity and inclusion," in the Metaverse. Disabled players, including Van Buren, have been slow to give Facebook the benefit of the doubt, and they want to know how the company will work on its expansion into VR spaces.

How setup can be a huge accessibility problem

Some disabled players' qualms with the Oculus storefront go even beyond burying essential features or building an accessible future. Jesse Anderson, who also goes by IllegallySighted on social media, is a visually impaired accessibility consultant who runs a YouTube channel where he discusses accessibility features in virtual reality. He's run into a number of issues just trying to set up his Quest.

Oculus and Facebook, in particular, have let a lot of disabled people who want to play VR games down.

Out of the box, new Oculus Quest 2 owners have to use their smartphone to set up their headset, which involves typing a code displayed in the headset into the mobile app. Anderson wasn't able to read the numbers and text in the headset. Without the kindness of a neighbor, he wouldn't even be able to use his new Quest.

This has been a recurring problem for him. He can't access any feature that's exclusive to the headset because they don't have the correct accessibility features. "There are some basic settings in the iOS app, but most of them are only available in the headset. I don't get to use those."

Oculus and Facebook, in particular, have let a lot of disabled people who want to play VR games down. It's emblematic of a greater problem in tech overall; a lot of accessibility features are made by able-bodied people without any input from a disabled player, developer, or consultant, and the platform holders are seemingly dragging their feet.

Facebook has a dedicated page for its accessibility team that it uses to publicize different accessibility-related updates. A majority of recent posts on the page have been small bios introducing members of its accessibility team, but if you dig far enough, the most recent VR-related post at the time of writing is about how they consolidated the headset's only three accessibility features into one menu in the headset's settings. Facebook has created resources for developers that work on accessibility features in their games, but to many disabled players this isn't enough.

Van Buren has spent some time talking to people who work at Oculus and isn't very impressed. "They don't really have a central accessibility idea in play. They're aware that it needs to be there," he said. However, knowing what's wrong isn't the same as acting on it. He sees Facebook's accessibility shortcomings as something that could be circumvented if it playtested its hardware.

Hardware's unique set of challenges can often be exacerbated by equally inaccessible software.

Hardware's unique set of challenges can often be exacerbated by equally inaccessible software. Van Buren recalls a time when a headset's form factor kept him from playing an early build of Job Simulator, "In the original Job Simulator demo, you had to throw things into a pot, and I couldn't look over into the pot. So I couldn't see." This meant he couldn't progress.

It was the first time that a game had ever been inaccessible to him as a wheelchair user. "Normally when I'm playing video games, I'm just using a controller or a mouse and keyboard; I don't need any assistive technology for that. That kind of opened my eyes to a lot of stuff."

What's being done

Considering Oculus is the most successful VR platform, there are a number of things Facebook could to to make its platform more accessible. Companies like Google and Microsoft have accessibility labs with resources and playtesters to help devs improve their games. Smaller studios and organizations rely on bringing in playtesters and consultants to round out what edges they can.

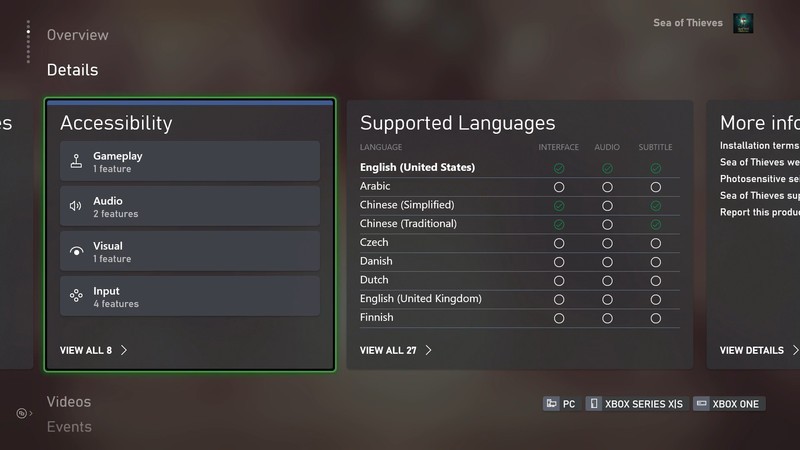

Outside of VR, more and more studios and companies are committing even more to accessibility in gaming. Xbox regularly publishes articles highlighting updates on accessibility across the ecosystem, with the most recent one published on Oct. 1 announcing it would add tags on the Microsoft store to indicate if a title had any accessibility features.

Since then, PlayStation's even thrown its hat in the ring with the PlayStation Store's new accessibility tab. Much like the rest of the gaming giant's pending re-entry into VR, very little is known how this might translate into meaningful change in the virtual reality space. At the time of writing, the page features a filter that allows users to look for "VR Optional" games with no mention of VR-only games.

Those universal, ecosystem-level features haven't hit most VR platforms yet — and without any platform holders enforcing or promoting strict accessibility standards or built-in hardware features, disabled players often rely on the developers themselves to do it.

Owlchemy, the developer of Job Simulator, released Shorter Human Mode a few years after the game came out, which adjusted the head height for players and allowed kids, short people, and people who can't play standing to access the game without any external tinkering or modification. That accessibility feature became standard in future Owlchemy games and helped steer the studio's output in a new direction. "Owlchemy's vision is VR for everyone," said company COO Andrew Eiche.

In many ways, Owlchemy's become the gold standard of accessibility in VR thanks to its commitment to inclusion. Nearly every source we spoke to for this article has mentioned the Google-owned studio as the best in the business.

For Anderson, what sets it apart is how willing it is to accommodate a variety of disabilities. "They are listening to people and they are trying to account for different things," he said. "It's clear that they put a lot of thought into making their environments pretty accessible."

The secret is Google's Accessibility Lab, where developers can playtest and refine a number of accessibility features, like subtitles and Shorter Human Mode. While few other developers have access to such a helpful resource, Eiche believes that Owlchemy learns the most when other people play the studio's games and give feedback.

The best way to make a game more accessible is to continually bring on disabled players and accessibility consultants to playtest it.

While he recommends that studios find accessibility consultants, he's found that even asking people to playtest their game will yield good results. Eiche believes "If there is a true secret of Owlchemy, even outside accessibility, it's our devotion to playtesting."

This hammers home what's been told to us from a number of sources: The best way to make a game more accessible is to continually bring on disabled players and accessibility consultants to playtest it. However, sometimes, accessibility is much simpler. Across a number of people working in VR development, stories of developers creating accessibility features by pure happenstance are surprisingly common.

Van Buren told me a story about the developers at Northway Games who created a new accessibility feature thanks to the original HTC Vive's controllers' limited battery life. At a certain point during a puzzle in its game, Fantastic Contraption, a controller's battery died during testing and they realized, "it was basically softlocked. They couldn't advance in the game because they couldn't complete the puzzle with just one arm."

Instead of moving forward with the game, hoping that players would just remember to keep their controllers charged, Northway decided to find a solution. Now, five years later, one-arm modes are fairly commonplace in many of the most popular VR games.

But accessibility solutions aren't always created from a problem. Sometimes, they're just a clever gameplay mechanic that happens to solve a specific problem. The Gravity Gloves in VR's most notable blockbuster, Half-Life: Alyx, are actually a creative means of making the game more accessible by allowing players to grab things without having to actually reach for it.

What's next?

In the world of console games, few developers have made as much of an impact on making accessible software recently than Naughty Dog. The Last of Us Part 2 garnered a lot of praise as a benchmark of accessibility thanks in no small part to its staggering 60 different accessibility features. Sony's other first-party titles haven't always followed suit, but the company remains dedicated to pushing accessibility forward.

In an interview with Wired, Mark Friend, lead user researcher at Sony Interactive Entertainment, discussed the future of accessibility in PlayStation games. He said, "every game released by PlayStation Studios is different, so our goal is always to ensure that we tailor our support to our studios and their games." This approach is what makes their entry into VR so exciting for disabled players and developers alike. It gives a lot of disabled players newfound hope that other developers will feel the need to catch up.

While it's been fairly tight-lipped so far, Sony's beginning to reconsider the world of VR with teases for its next-gen PS5 VR headset. There hasn't been a lot — just a few product shots — but with Sony re-entering the ring, the promise of more accessible VR games is tangible.

Players and developers alike are hopeful that new competition will light a fire underneath Facebook and Oculus more than anyone else as the social media conglomerate turned data collection company proves to be one of the greatest barriers confronting disabled players. People like Brian Van Buren and Jesse Anderson feel alienated by the company's corporate approach to accessibility.

Van Buren specifically cites their, "Walled garden approach to development," as what's most concerning about the future of Facebook's accessibility efforts. It hammers home what every disabled player knows well: accessibility that's created by able-bodied players and developers isn't going to serve disabled players well.

Relying on industrial competition to push accessibility forward is a slippery slope. Without corporate outreach programs like Xbox's introductory accessibility course for developers and educators pushing to make gaming more accessible, the rising tide will sink all but the biggest ships.

Fortunately, as more companies begin to emphasize accessibility, there's an increasing demand for developers who understand how to implement creative solutions. "There's some definite movement, and the competitive nature of the companies is helping to move that along," said Cyndi Wiley, digital accessibility lead at Iowa State University. As an educator, she believes in the promise of introducing a new generation of designers and creators to new ways to make their work more accessible.

Between more developers and designers learning about accessibility and more publishers facing pressure to include accessibility features, VR can only become more accessible. The ripple effect that big studios making VR games have is almost immediately visible in the video game industry at large, especially since first-party Sony games tend to have a fairly high attach rate. When a game sells well on a platform, that attracts bigger publishers and developers, who can put more money into developing accessibility features. Soon, we might see those results.

Charlie's a freelance contributor at Android Central from Milwaukee, WI.