Would you want your mom to see this? - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Social

Would you want your mom to see this?

Even after nearly a decade of modern social networking, we're still having trouble grappling with privacy. We're not talking about when some server is compromised and your password ends up for sale in the seedier parts of the internet — no, this is about our own management of our own privacy.

What are we supposed to be posting on Facebook and Twitter and Google+? What shouldn't we be posting? Can we depend on the privacy features these social networks offer, or should we just assume that if we post it online behind supposedly closed doors that it's not necessarily going to stay behind those closed doors? And once it's online, is it yours anymore anyway?

Do our employers have the right to see what we're posting online? Should they care? And how are we supposed to teach our children how to properly and safely use social networking when we're clearly failing at doing so ourselves?

Social networking can be awesome, and it can be dangerous. Just how are we supposed to manage our own social privacy?

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Let's get the conversation started!

By Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson & Rene Ritchie

Play

Social Privacy

Social Privacy

- Work and social

- Online privacy

- Video: Christina Warren

- Content ownership

- Video: Dalton Caldwell

- Kids sharing

- Video: Georgia

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

Now hiring: workers with clean Facebook profiles

Currently, at least in the United States, this idea that an employer can compel an employee to reveal the private contents of their social networks as a condition of employment is technically legal. The United States Congress had a bill proposed to amend FCC regulations on the matter, but it was struck down, clearing the way for the continuation of what many would say is an invasive tactic by employers.

A Beacon in the dark

Facebook has faced criticism numerous times over its privacy practices. The biggest backlash came in 2007 with the surprise launch of Beacon, a system that allowed third-party websites to send information on your actions to Facebook. Participants in the program included retailers and game publishers. While the opt-out data sharing would have been considered invasive enough, Facebook faced considerable scorn over Beacon's automatic publication of that information on a user's news feed.

Within a month the backlash had proven strong enough that Facebook retooled Beacon to require confirmation before any activity information was posted. Shortly afterwards Facebook was accused of storing data from Beacon even when users had opted out. Facebook denied the charges, but outside websites were already dropping the program. Beacon was shut down less than two years later as part of a class-action settlement.

The notion of whether or not this is a "right" is a legal one and laws can be written or overturned through the democratic process. Therefore, the notion that companies can force you to reveal your Facebook password as a right is purely relative — we can just as easily make it illegal as well, ergo not a right.

Is this the kind of work environment that we want?

The question should be: is this the kind of work environment that we want? Sure, we understand that an employer may take umbrage at something posted publicly by an employee that could reflect negatively on them — after all, "at will" jobs are just that. But this overreaching of companies into the private lives of their employees reeks of servitude and surrendering of one's freedoms for the "privilege" of working.

But so long as the economy is weak, specifically with high levels of unemployment, the employer will always have the upper hand to dictate the terms and conditions — after all, if you won't give your Facebook password for a job, surely someone else will. Since labor unions, which traditionally have defended workers, are increasing out of vogue, it will be up to the masses or legislative bodies to act. Neither of which look likely anytime soon.

Q:

Does your boss have the right to your Facebook password?

313

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Don't post anything you wouldn't want your mother to see

Everything on the internet is public. It's 2013, we all know this by now, right? Everyone from politicians to business leaders to celebrities to athletes have been caught with their pants down, figuratively and literally, online and even in court, thanks to something they posted online. Big brother is here, and he's brought along little brother — all of us, online with cameras, all the time — just to make certain our every private moment can be viewed on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube.

Even if you truly believe your online activities can and will remain private, it's safer to assume the opposite. One mistake, one careless moment, one lost device, one hack, and everything and anything can be compromised. And once it's public, there's no going back.

The easy answer is never do anything that that you couldn't survive if it went online. But that's not practical, and it doesn't account for all the shades of gray.

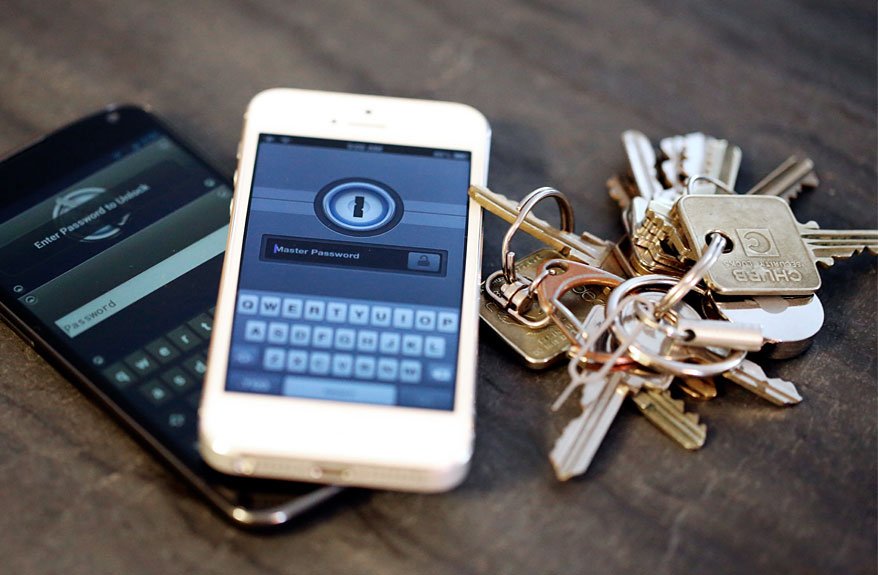

Forming a password

While it's an imperfect practice, passwords currently form the backbone of online user authentication. When building a password, users have to weigh complexity for security against their own ability to remember the password. Additionally, it's recommended that one use different passwords for different websites, so that if one is compromised it doesn't open all the rest of their accounts as well.

Passwords should avoid common words and names (especially of family), contain numbers, upper and lowercase letters, and special characters (parentheses, ampersands, semicolons, etc). The more complicated a password, the harder it is to crack. A ten-digit password that consists entirely of lowercase letters — say, talkmobile — would have 141 billion possible combinations, taking only a few seconds to calculate them all through brute force guessing. e#X9%f)Dl3, with lower and uppercase letters, numbers, and special characters, ups the possible combinations to 60 quintillion, which would take days, if not weeks to calculate.

Many have made the mistake of thinking personal means private, that posting something on a personal Facebook page means it'll remain between you and your friends. But downloading, copy-pasting, and screen captures are never more than a click away.

Companies are looking at Facebook pages now. That jerk friend of who shot video of your drunken dance on top of that Chevy in Mexico? They'll see it. Significant others are scouring Twitter timelines. That hottie at the party who flirted with you and snapped a quick picture? It'll be online.

Back when I grew up, when I did anything dumb, only the people there saw it. Now all of us are only ever a moment away from being the next "Star Wars Kid."

All of us are only ever a moment away from being the next 'Star Wars Kid'.

For kids these days, online is just a fact of life. A good contingent of them use the internet nonstop — there's little to no thought given to how what they're doing online right now will impact them years from now.

Here's the thing though — the same rules still apply. Digital you is largely inseparable from real life you. Don't do anything online that you wouldn't do anywhere else.

And if you do, hope so many other people are doing it as well that your awkward, embarrassing, or flat-out illegal moments get lost in the noise of billions of other posts…

My advice has always been: Be yourself as much as you can, but think about whether you'd want your mom to read this.

- Christina Warren Senior Tech Analyst, Mashable

Q:

Has anything you've posted online come back to haunt you?

313

Rene Ritchie iMore

Your content is no longer your content

We don't own our stuff. Not when it's online. Not when it's hosted on someone else's servers. We like to think we do. We like to translate old-fashioned, real-world concepts of ownership to new-fangled, virtual goods and pretend like our values will be honored and respected. It comforts us. But it's not the truth. The reality is about as far from the truth as it could be.

The truth is, anything we put online is immediately and irrevocably no longer ours. Morally, even legally at times, it might be called or considered ours, but realistically and effectively it's not.

Anything we put online is immediately and irrevocably no longer ours.

77 million

For all that we do to control our online footprints, things can get out of our hands — and the hands of others.The first major data breach came in 2005 with the theft of an Ameriprise Financial laptop with 260,000 customer records. The next year saw breaches from Boeing, Ernst & Young, and AOL. But it was a theft of a US Department of Veterans Affairs employee laptop that exposed the names, Social Security numbers, and dates of birth of some 26 million US military veterans and military personnel.

The years since have seen accidental data exposures by retailers, hospitals, banks, social networks, and even governments. In 2011, the biggest known breach to date impacted the Sony PlayStation Network. Sony shut down the network on April 20th, revealing that the days prior had seen an intrusion that exposed personal details of all 77 million accounts. The full breadth of the breach was unclear, though Sony indicated the possibility of compromised credit card data. The network was offline for 24 days while Sony retooled the system.

That's why it should come as no surprise that Facebook, Google, Instagram, and others have faced strong reactions when they've updated their terms of service or engaged in practices that made people uncomfortable. Frustratingly, those terms of service updates have sometimes even been to update the previously vague protections afford to users, but outrage forced the service to back down in the face of a revolt.

Innately most of us just know we don't want our casual, personal photography used or licensed out for use in ads, even in-network ads. We don't want our information shared with divisions of a company, or third-parties that we don't know and have no reason to trust. We feel betrayed when the contact information in our address books is uploaded without our express permission and used in a way that compromises our friendships and relationships. But selling and reselling our personal information is nothing new - corporations had been doing it for decades before the internet came along.

In all of these cases, reality is far less important than perception, logic than emotion. Terms of service are documents we skip through to get to a cool app or service. Respected is how we feel using that app or service. In the age of free-as-in-Google-or-Facebook, where they provide hosting but we provide everything worth hosting, that's the only way things can work.

50 or 60 years ago you could move to a new town and change your name and you really could have a new identity. That obviously doesn't work anymore.

- Dalton Caldwell Founder and CEO, App.net

Q:

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile social communications

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Children don't know what not to share unless we tell them

This may be the most important issue of this era. Social has exploded in the past five years or so, and suddenly we have a generation of children growing up with their entire lives documented online, at the hands of their parents and increasingly at their own hands. Those of us who were around before the Internet can remember a time when our exploits weren't caught on camera and immediately uploaded to YouTube. A time when we didn't broadcast every thought without thinking. And a time when it wasn't easier than ever to to prey on the young and naive.

The late 1980s and early '90s were all about safe sex. Nearly as important is the burgeoning era of safe social.

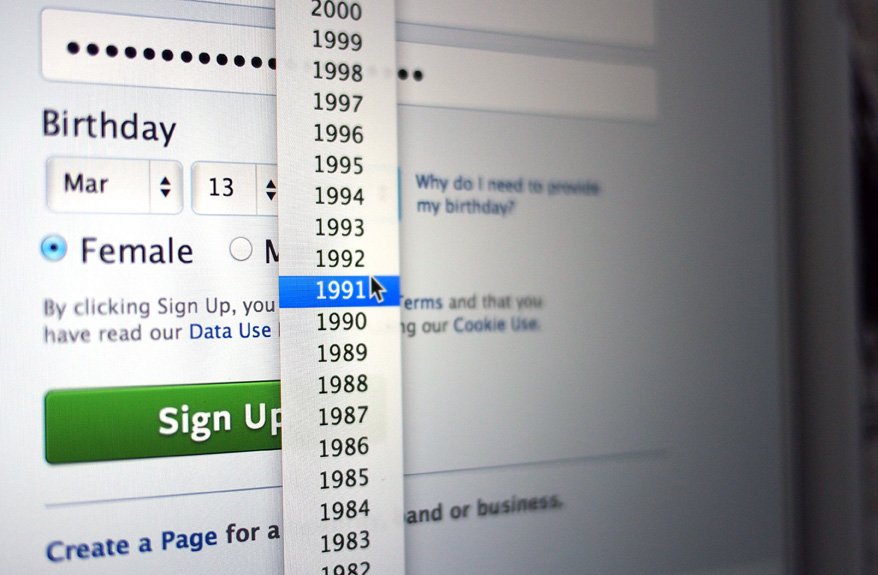

Please verify your age

Facebook's policies restricts membership to users 13 years of age or older. But what does it take to verify one's age when registering for Facebook? You tell Facebook how old you are — there's no outside verification of that provided age. As such, there are millions upon millions of user accounts that belong to kids under the age of 13.

There's no national records database of children of that age, and for good reason. The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 exists expressly to prevent companies from storing the information of underage users. So when somebody attempts to register a Facebook account and provides information with a birthdate younger than 13, Facebook doesn't save that data, inadvertently allowing the kid to try again with an earlier birth date.

What do you share? When do you share it? What is privacy? Does it even exist anymore? We live in an era where you should expect that anything you do or say outside of your bedroom (hell, not even then) could become public at any given time. That's the harsh reality, and it's not fair. So who protects the children? Who educates them?

We're in the awkward adolescence of the social era. Some folks get it. Some don't.

It has to start with the parents. But, again, we're in the awkward adolescence of the social era. Some folks get it. Some don't. Others are still getting their sea legs. Or, worse, some parents are the problem. Maybe they're not on Twitter and Google+, but it's likely that one or both parents are on Facebook. You don't have to look too far to find tales of "shaming," in which a parent takes to the public arena to say "Look at this dumb thing my kid did! I'll tell everyone! That'll show 'em!" While shame has its roots deep in traditional religion, social shaming's not quite out of Dr. Spock's manual.

Point is, for many parents the Internet and children remain uncharted territory.

At some point, Internet — and thus social — safety has to become a part of standard curriculum. It'll have to be taught alongside math and science and English. It can't be relegated to the back rooms of home economics and typing and computer literacy. Or, worse — our children can't afford to not be taught importance of privacy and security. The importance of understanding that not everything you see or do or say is meant to be shared in public.

In the end, the best way of protecting your children is to be aware of what they're doing.

- Georgia Therapist, Host of ZEN & TECH

Q:

What's the best way to protect children online?

313

Conclusion

Even after years of social networking, we're still unsure of how best to navigate the waters of online privacy. Generally the best policy is the simplest one: if you don't want it online, don't put it online. Though sometimes that's easier said than done. Everybody has a smartphone with a camera these days and access to the internet, and sometimes not the forethought to stop before posting. It's all too easy to put something too damaging in all the wrong places.

Our families are watching. Our friends our watching. Our bosses our watching. The world is watching, and more than ever we have to watch ourselves and each other. And our kids are watching; not only do we have to be careful about what we put online to protect ourselves, we have to be careful about the example we provide for children.

Social privacy is tricky. Knowing what to share and when to share it, and what not to share and when not to share it is an evolving concept for each of us. So, where do we set the boundaries?