Whenever, wherever: Why you can't just use any phone on any carrier - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Carriers

Whenever, wherever: Why you can't just use any phone on any carrier

Chances are you've encountered it at some point. You go out into the country, or into a certain part of town, and you lose signal from your carrier. But another network is out there, and it picks up the slack. You're roaming.

Unlike the buffalo of yore, roaming onto other carriers isn't a carefree experience. It wasn't until recently that no-cost-to-you roaming agreements were in place for most major carriers, at least domestically. International roaming's a different beast, and as it would turn out, a very expensive one.

Things have been complicated by the introduction of varying implementations of LTE. The phones might support it, but the carriers being large multinational telecommunications conglomerates are slow to adapt to changing circumstances, even if they've already overcome similar circumstances before.

So what's it going to take to have more devices that support every carrier? What's holding up LTE agreements? And just why is international roaming so damn expensive?

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Let's get the conversation started!

by Rene Ritchie, Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson

Roaming

Articles navigation

- Cross-carrier devices

- International roaming

- Video: Alex Dobie

- LTE roaming

- Fixing roaming

- Video: Simon Sage

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Is it too much to ask for my phone to work on any carrier?

Let's start with the science. Cell phones use radio waves to move data from the towers to your phone. There are two major protocols for the tech that does this. One is called CDMA — think Sprint and Verizon here in the U.S., but not forever — and the other is GSM — that's T-Mobile and AT&T here in the States. The oversimplified explanation is that you either use one or the other. Sprint and Verizon phones technically can't work on AT&T or T-Mobile's networks.

It gets a little mixed up when you start talking about modern smartphones (as in a year or two old) on Sprint and Verizon here in the US. LTE data works over GSM, so we have phones that run on CDMA and LTE sort of (but not really) simultaneously. And many of these phones actually sport both CDMA and GSM radios, simply to save on manufacturing complexity.

Where the GSM and the CDMA roam...

Simply put, roaming is using your phone and service subscription to one carrier through the network of another. Compatible carriers often implement roaming agreements to enable the sharing of towers in areas where they lack adequate coverage. This allows users to have a more-or-less seamless experience, even if they're out of their own carrier's coverage zone.

While CDMA carriers like Sprint and Verizon can roam onto each others' networks, roaming is primarily the domain of GSM carriers. In the United States not only do big national carriers like AT&T and T-Mobile have roaming agreements (though theirs is limited in scope), but smaller carriers like Metro PCS and regional carriers such as Cincinnati Bell also have roaming agreements. These regional roaming agreements help reinforce national network coverage in certain areas as well as provide national coverage to regional carriers.

The other issue is the matter of frequencies. The phone you're using has to be able to pick up the frequencies that a carrier is using. And not every operator uses the same frequencies.

But the fact is that the science is mostly taking care of itself. CDMA is on its way out. Not quickly, but it's going. The truth is that for most folks, this isn't a huge deal anyway.

Like with anything else in this business, it comes down to money.

That's the science. And it's not really the reason why phones don't "just work" on all operators. Like with anything else in this business, it comes down to money.

Most phones in the U.S. are "SIM-locked." That is, they only work with a SIM card that came from the same carrier. Buy the phone from T-Mobile? You'll need a T-Mobile SIM card. Same for AT&T, O2, Telefonica, and MTS.

To use another operator's SIM card, you'll need an unlock code. This is what keeps you from buying that hot new phone that's only available on one operator and then using it on another. And it's a shame.

Want to avoid all that? Buy SIM-unlocked phones. They might cost more. Or, in the case of Google's "Nexus" program, they might cost far less. But either way, they'll give you the freedom you deserve.

Q

Does multi-carrier compatibility factor into your buying decisions?

876 comments

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

International roaming is expensive for no good reason

Why is roaming so expensive? Because it can be, that's why.

What we're talking about here is international roaming. In most countries the carriers have agreement to cooperative roaming - I'll let you roam on my network if you'll let me roam on yours. It hasn't always been that way, but it generally is today and we're better off for it.

When you cross the border with that phone, though, look out, because roaming charges are coming. Certainly, there are some expenses the carriers incur in your using towers in a distant land. After all, your data has to be slipped over the border in the dark of night, lest it be caught by border patrol agents. It's that or risk your bytes being confiscated at the border crossing.

Oh, wait, that's not how it is. Here's the thing about international roaming: it costs as much as it does because the carriers can get away with it. All of our communications are handled digitally these days - it doesn't matter if it's calls, texts, or internet data - it's all handled over the same radios, microwave transmissions, and the fiber lines that cross the border.

International roaming costs as much as it does because the carriers can get away with it.

There's absolutely no reason that international roaming costs couldn't also be nonexistent. If AT&T and T-Mobile can get along, or at least not pass their commiserate roaming charges on to the customers (you roamed on AT&T, but one of their guys roamed onto T-Mobile, so we'll call it even), there's no reason AT&T in the US and Rogers in Canada couldn't come to the same sort of understanding.

Baby Bell Verizon

Like AT&T, Verizon Wireless can trace its roots back to 1877 and the American Bell Telephone Company. AT&T's nationwide wireline monopoly was broken up in 1984, splitting the company into seven technically independent "Baby Bell" regional telephone operators with a common AT&T national long distance partner. Bell Atlantic covering Pennsylvania to Virginia and NYNEX had New York to Maine; the two merged in 1996.

Bell Atlantic launched their own wireless network in 1997, and two years later announced plans to merge their Bell Atlantic Mobile and PrimeCo Personal Communications wireless services with UK-based Vodafone's AirTouch Cellular and Paging. The joint venture received regulatory approval and launched in April 2000 as Verizon Wireless.

Just two months later, Bell Atlantic merged with GTE (a telephone provider that had operated independently under the Bell System) and rebranded as Verizon Communications. Over the next decade Verizon systematically sold off portions of the old Bell Atlantic and GTE wireline business, and today offers landline service in just 11 states. In addition to national wireless coverage, in 2006 Verizon began offering a FiOS fiber-to-the-home service for internet in television service in select locations.

It's not unlike text message charges. It costs the carrier a fraction of a fraction of a penny to process a text message (they're sent over the band the phone uses to communicate to the tower that it's there). But because we have no other option until one changes their mind, we're forced to pay what is an exorbitant sum in comparison to their cost.

International roaming is even more of an over-a-barrel moment, as it affects a small portion of customers a small portion of the time. And because they have no other option, they either pay or don't use their phones (and what hell that is).

If your phone is SIM-unlocked and compatible with a local carrier you can sometimes get a throwaway prepaid SIM for international travels. But if your phone isn't, open your wallet.

The main reason roaming is expensive is that carriers around the world decided among themselves that it was going to be expensive.

- Alex Dobie / Managing Editor, Android Central

Q

How do you pay for data when you travel internationally?

876 comments

Rene Ritchie iMore

The messy politics of LTE roaming

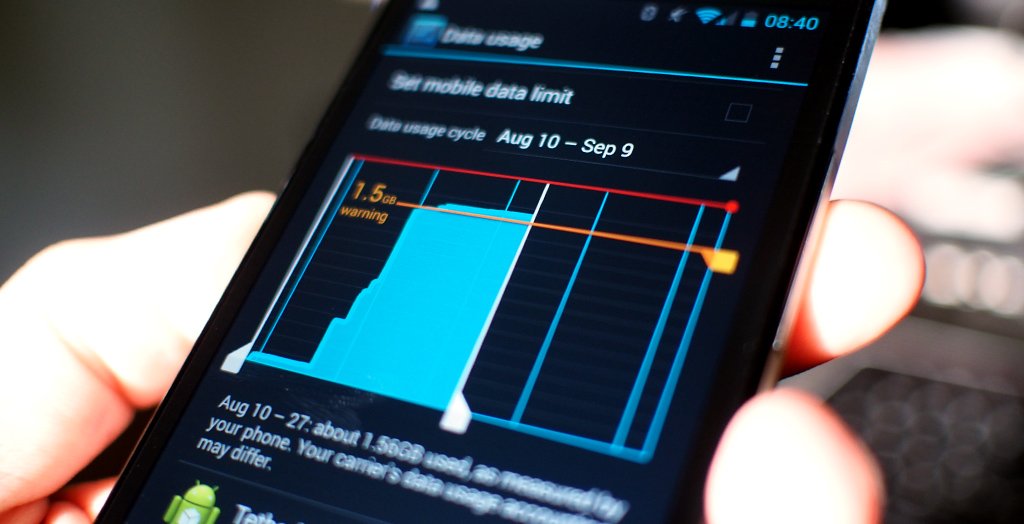

I love LTE (Long Term Evolution, proper 4G cellular data). I can sit in the local coffee shop and pull down 50mbps. That's faster than a lot of home internet connections, even with the data cap. The point is: zoom zoom.

I live in Canada, an hour from the border with the United States. When I cross over, my blazingly fast LTE vanishes and my phone drops to 3G. There is plenty of LTE coverage in the US, but my perfectly capable phone can't roam onto it. It's the longest undefended border in the world, but woe if I could use AT&T's equally-blazing LTE towers.

While LTE is technically an open standard, LTE isn't standardized at all when it comes to frequencies.

There is a technical consideration. While LTE is technically an open standard, LTE isn't standardized at all when it comes to frequency bands - there are 30 different segments used by different carriers worldwide. This was a problem when early LTE phones had limited band support. Newer LTE chipsets support many more LTE bands - that's why companies like Apple and Samsung can make two or three versions of the same phone and cover most of the world. Newer chipsets are supporting even more bands; conceivably the number of models needed will drop closer to one.

Sadly, however, there's a bigger and ultimately more frustrating issue: there are no LTE roaming agreements in place. Well, no, I take that back. My carrier, Rogers, was the first North American carrier to offer LTE roaming, it's just limited to the carrier 3. In Hong Kong. Thanks for that.

3GPP Long Term Evolution

The first 3G GSM cellular standard was released in 2000 as UMTS. By 2002 the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) had upgraded that to HSDPA, providing even faster downloads, followed in 2007 by the faster still HSPA+. Technically speaking, HSPA+ is capable of up to 168Mbps downloads, though the fastest any carrier has implemented has been a still-fast 42Mbps.

2008 saw the introduction of Long Term Evolution, the first "true 4G" standard. LTE, technically capable of speeds up to a blistering 300Mbps (good luck ever seeing that, though). While some carriers initially implemented the competing 4G standard WiMAX for their networks (especially CDMA carriers), more and more LTE has become a standard for 4G worldwide, with even CDMA carriers like Verizon and Sprint adopting it.

My phone won't work on another carrier not because of any technical issue, but because the carriers haven't signed a piece of paper yet. Canadian carriers were deliberate in choosing LTE frequencies that matched those used in the United States, yet there's no LTE roaming.

They could be worried that there's not enough LTE spectrum to handle roamers, though that seems silly given the sorry state of 3G networks past, and how little roaming was ever a factor. They could be discussing how much they'll charge for the privilege of roaming on LTE, which eats data quickly, and how they'll divvy up that money.

Either way, big companies move slowly.

Verizon has said they're hoping to get LTE roaming agreements with at least a few other carriers in North America, Europe, and Asia by 2014. Presumably other carriers will follow suit.

Q

Would you be willing to pay for LTE roaming?

876 comments

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

We have the devices, just give us the roaming

The question of roaming and whether it even needs to be fixed of course depends on your personal situation. By and large, in most developed countries the carriers have established networks that cover a comprehensive portion of the population, and have no-cost-to-the-customer roaming agreements with carriers that plug their dead zones. International roaming is another question, but that's a matter of corporate politics.

Data roaming is increasingly becoming an issue. While carriers have all manner of free domestic and paid international roaming agreements for 3G, they're all but nonexistent for 4G. There is the matter of differing frequency bands between carriers, and while that might mean that O2 in the UK isn't compatible with AT&T in the US or China Unicom, more and more the smartphones themselves are bridging that divide with expanding band support on a single device.

The manufacturers aren't doing this for your benefit, of course. They know that international roaming is a small portion of their customer base, small enough that it's not often a selling point. What drives their expanding LTE band support is economies of scale - the more bands you support on one device, the fewer versions of that device you have to make for different carriers, and thus the more money you can save by reduced manufacturing complexity.

It's hard to deny that there's not corporate competition at play in selecting differing LTE bands.

The reasons for carriers having different LTE bands are many. It's hard to deny that there's not corporate competition at play in selecting differing bands - it meant that it was easier early on to lock a device to their network through mere hardware support.

A baker's dozen of bands

While UMTS, HSPA, and HSPA+ operate on a handful of frequencies around the globe, a mix of factors led to LTE being split amongst a dozen bands worldwide. In North America carriers use the 700, 800, 1900 and 1700/2100 MHz frequency bands - shorthanded as bands 4, 12, 13, 17, and 25.

That's not the same as in South America, where LTE runs on just the 2500MHz frequency, or Europe where you can find LTE variously on the 800, 900, 1800, and 2600MHz slices of the radio spectrum, otherwise known as bands 3, 7, and 20. Australia and New Zealand are just in the 1800 MHz block, otherwise known as bands 3 and 40. That's nothing compared to Asia, where while LTE operates exclusively in the 1800 and 2600 MHz range, it's split into bands 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, and 40.

All told, carriers around the globe operate LTE on thirteen different bands spread out over more than 800MHz of spectrum. No one radio chipset today supports all of these bands (in addition to CDMA, GSM, EvDO, UMTS, HSPA, and more), but increasingly fabricators are building radios that can work on more and more frequencies.

There's also a fair amount of government politics here- the frequencies used by LTE today were almost universally used for something else before. Each government acted independently to free up old frequencies - in many cases analog TV broadcast licenses were killed in favor of LTE licenses.

The only way to fix LTE roaming in 2013 is for these big slow-moving companies to put together agreements to enable it. The hardware in our smartphones supports it, and is supporting more and more of it every day. While governments could step in and mandate support from smartphone manufacturers and cooperation amongst the carriers, all that would do is hastily speed up the process. We're getting there, it's just going to take a while.

We pay some of the highest data roaming charges in the world. It's kind of rough.

- Simon Sage / Editor-at-Large, Mobile Nations

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile clouds

Conclusion

There's no doubt, roaming is broken. But it's just one part of a broken system, one that only persists because we believe we have no other options. Just when it seemed like we were getting domestic roaming under control, LTE came along and set us back to where we started.

International roaming has never been good. Devices that support multiple carriers have proliferated over the past several years, even bridging GSM and CDMA with a single device. Even LTE, still in its infancy and with roaming seemingly crippled by a plethora of bands, is comprehensively supported by modern devices.

It's in the best interests of customers and manufacturers to have devices that support as many frequencies as possible. More frequency support means fewer models for the manufacturer to support, and it means better compatibility for the customer. The problem is the carriers. They're almost universally incredibly old companies, rooted in ancient wireline industries and with all of the corporate politics that come with it.

The key to fixing roaming, both domestic, and international, 3G and LTE, is simply to get along.