The death of privacy: The internet is always watching, and it never forgets - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Security

The death of privacy: The internet is always watching, and it never forgets

by Rene Ritchie, Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson

Our smartphones and tablets are increasingly becoming repositories of our personal information. It's a treasure trove of data that could be used to build a frighteningly complete picture of you as a person. It's more than just your contacts, calendar, memos, and photos - it's your web history, your calls and text messages, your banking data and social network logins.

People say "my whole life is on my phone", and while that hopefully isn't entirely true (time to reevaluate your priorities if it is), an increasingly large portion of our lives - or at least the data that comprises it - is finding residence on these devices. So just how are we going about keeping it all secure?

How do we deal with the threat of the less-than-thoughtful people around us, let alone the government's intrusions? How do we keep our devices and the accounts on them secured? And how do we train our children, the ones that are growing up in a world where ubiquitous internet is a fact of life, to understand the real threats that exist on the internet and how to protect themselves?

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Let's get the conversation started!

Privacy

Articles navigation

Rene Ritchie iMORE

Big Brother? What about Little Brother?

There are benefits to ubiquitous mobile recording devices, to be sure. Be they phone, tablet, or wearable, the ability for everyone and anyone to capture real-time news and record events as-they-happen is invaluable to history, journalism, and even law enforcement. If we, as humans, were perfect, with unimpeachable morality, unassailable ethics, and unquestionable motivations, it could be the single greatest advancement for society, not just technology, that we've enjoyed since the printing press.

We're the assholes who find as many deplorable, despicable, desolate ways to abuse these breakthroughs.

But we're not. We're the assholes who snap pictures of each other in changing rooms, who post videos of kids pretending they have lightsabers, who wrongly identify bystanders as suspects, who release recordings of people famous and unknown at their worst, and who find as many deplorable, despicable, desolate ways to abuse the breakthroughs we've achieved as we do exemplary, meritorious, and glorious. In many ways our fellow humans are worse than Big Brother - it's not often that we worry about the government publicly elevating-by-demolishing our reputation with a compromising photo or video.

Incontrovertible proof

The advent of the camera phone has revolutionized news gathering and telling. Firsthand sources now have more than just their word - they often have images or video of what they're describing. Camera phones have captured all manner of important, grisly, and embarrassing events, often making worldwide news.

The 2006 execution of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein was captured with a mobile phone and ended up online in just a few hours. 2011 saw the capture, brutal abuse, and eventual death of overthrown Libyan president Muammar Gaddafi at the hands of a Libyan rebel militia.

New York Congressional Representative Anthony Weiner was brought down by a sexually suggestive photo of himself posted onto Twitter in 2011 from his smartphone. Weiner claimed for several days that he had been hacked before finally admitting that the photo was of him. It took the leaking of a second photo (again, taken with his own phone) before Weiner resigned from office.

The power provided by modern mobile recording technology brings out both the best and worst of us. Every moment where the deaf can video chat or the blind can use voice control or parents can see their children or loved ones can hear each other's voices from across the globe is purchased by an equal and opposite moment of tyranny, betrayal, and bullying.

It's not the technology we need to worry about. It's not even each other. We have control over neither. It's ourselves. The only way to avoid worrying about "Little Brother" is for each of us, every day, every hour, to refuse to be a "Little Brother" that needs to be worried about.

In other words, to quote Wheaton's law: Don't be a dick.

Q:

Are you concerned about pervasive government internet surveillance?

876 comments

Daniel Rubino WINDOWS PHONE CENTRAL

Security layer number one: you

The issue of computer security is will increasingly grow more complicated and imperative as we place more and more of our personal lives "online" or in the cloud. From banking to travel information, shopping history to browser syncing, the amount of information we share and enter online is simply staggering. But how do we best to protect that information?

Tried and true methods from years ago still apply today, including using unique passwords, having those passwords utilize alpha-numeric variations (e.g. upper and lowercase, special characters, and numbers), not storing them in an unencrypted file, and certainly not using a short and simple password.

Today there are a few password manager apps like LastPass and KeePass that work across traditional desktop operating systems and browsers, and even smartphones like Android, iOS and, Windows Phone. These password lockers can do the work for you in entering your account information as the user only needs to remember one long master password. Of course, such a scenario also means all of your passwords are listed somewhere and in theory, it can be hacked in one fell swoop.

Common Access Card

Beginning in 2000, the United States Department of Defense began replacing the laminated paper ID cards of DoD employees and members of the US armed forces with the new Common Access Card. The "CAC" is a standard-sized ID card, bearing the owner's photo and basic service info (rank, branch, etc), along with several different technologies to verify the owner's ID.

The CAC has two barcodes: a stacked linear PDF417 barcode on the front and a standard retail-style Code 39 on the back. The back also bears a magnetic strip that can be programmed for local security system access. The front has a distinctive Integrated Circuit Chip that is used to interface with smartcard readers for secured computer access. The ICC has a capacity of 144KB and carries authentication certificates protected under a 2048-bit encryption scheme. RFID technology is also integrated into the CAC; though it is rarely used, new CACs are issued with a paper sleeve lined with a layer of radio-blocking copper.

With more than 3 million active CACs in circulation, the DoD is the largest issuer of two-factor authentication devices in the world.

Features such as two-factor authentication are becoming more widespread, though not optional. Two-pass authentication requires the user to enter in a password but the service may also call or send a text message to your cell phone with a unique-for-this-login security code that you also need to enter. Such methods, while a bit clumsy, go the extra step in making sure you are really you.

Another method is the use of a physical "key" like YubiKey, which requires the user to connect the device up to their computer to "login" to services like LastPass. Two-factor security models dramatically amp up the effort required to access your secured accounts and data, though you pay for that security with diminished convenience.

The more security stratums you have in place, the better.

And really, that is the secret right there: layers. The more security stratums you have in place to protect your information, the better off you will be. There may never be a single solution — even biometrics are a mixed bag these days — which means it will be up to the user to throw up roadblocks to the would be hackers of the world.

Q:

How do you manage all of your passwords?

876 comments

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Prove to me you are who you say you are

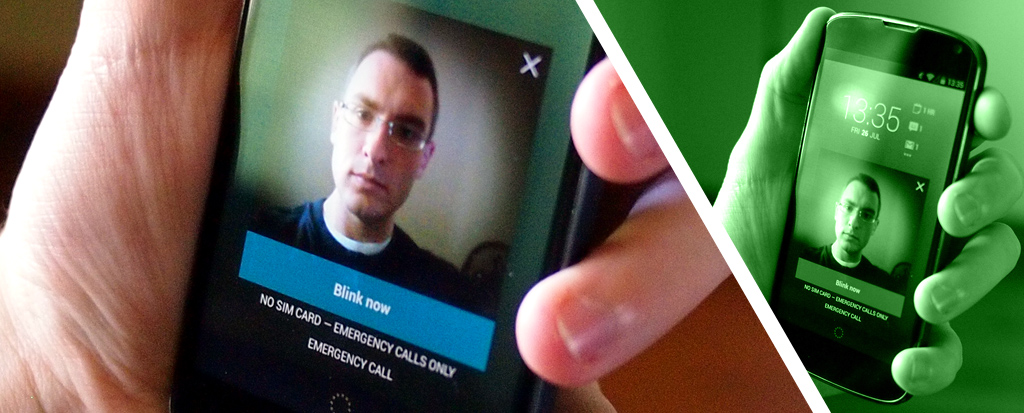

Security on mobile still sucks. We're limited to entering numbers for a PIN lock or maybe a real password or tracing a pattern on a little touchscreen, or taking a picture of our own face, just to unlock our devices. Add up the hours spent in a year by humans trying to enter passwords on mobile devices, and you'd get a ridiculously big number.

Since password entry on mobile by-and-large sucks, people often dumb down their passwords, making them less secure. They turn to password managers which often don't have the same capabilities on mobile as they do on the desktop, or just turn off or save all the passwords they can, resulting in phones and tablets that, if lost or stolen, are totally unprotected.

That doesn't even take two-step or multi-factor authentication into account. Ever watch a normal person try to use that? It's like watching a puppy be subjected to torture.

Just swipe your finger

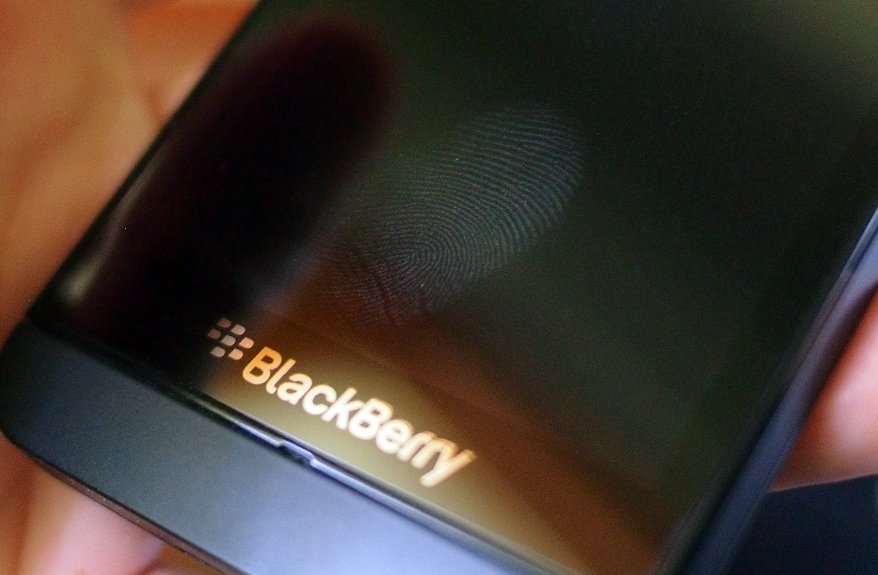

In mid-2013, both Apple and Samsung (and LG and…) were rumored to be working on integrating fingerprint scanners into their flagship smartphones. The rumor's been heralded as a breakthrough for mobile authentication, providing a form of identification that's much harder to break than a PIN lock, though neither phone would be the first to integrate fingerprint scanners.

No, we're not talking about 2011's flub, the Motorola Atrix. This is about Fujitsu, who has shipped more than 30 phones that integrated fingerprint sensors. Fujitsu's first fingerprint-scanning phone incorporated technology from AuthenTec (purchased by Apple in 2012, thus spurring the rumors we're talking about today) and was released in 2003. Granted, the Fujitsu Mova F505i was a Java-powered flip phone, but for the time it was pretty advanced.

Security on mobile, for individuals, is horrible. It needs to be fixed, and that fix has to come from the OS makers. It has to be baked in, and it has to be as strong and as convenient as possible.

So how do we get there? Basic password management has to be built into the platform at the system level, so it can be everywhere and access everything. Think 1Password or Lastpass at their most basic level, usable by all the built-in and third-party apps. Any time anything on my phone or tablet needs a password, the system-wide manager should pop up, take my master password, fill in the specific account information, and let me get on about using my device.

Basic password management has to be built in at the system level.

It should also be abstracted enough that while, for now, a master password unlocks everything. One day biometrics can take its place and a fingerprint or iris scan can take on that job.

Identity is becoming a big deal on the internet. Proving who we are will be the key to online commerce. Mobile is going to play a big part in that. Once security in mobile works, your phone can prove who you are, and then unlock other services and devices around you. Just like you show a drivers license or passport today, mobile will be the ID tomorrow.

That's why mobile security has to be improved now. It has to be made simple, and it has to be made seamless.

Q:

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile security

Phil Nickinson ANDROID CENTRAL

Supervision and education are the keys to safe online kids

It's time for a new digital revolution. The 1980s in America were the "Just say no" years in the fight against drugs. In the 1990s, it was all about safe sex education. The proliferation of the Internet — and moreover, broadband Internet — of the aughts brought us all together like never before, but often in nameless, faceless ways. Those were easier times and our advice to children and adults could be summed up with the likes of "Don't tell people your real name," and, "Don't give out your address."

But we now live in a time in which sharing anything and everything isn't just accepted — it's expected. And if you take a minute to think about that, it's truly terrifying.

"Put it on Facebook, Dad!" is a constant cry in my house.

"Put it on Facebook, Dad!" is a constant cry in my house. Kids want to see and be seen. Nothing wrong with that, of course. That's why all these social networks exist.

But someone has to teach our children that not everything needs to or should go online. That starts, as it should, with the adults. Computers and tablets should be in common rooms of the home. They should be password protected. Children should only use them under supervision. And they should be taught to, above all else, not be afraid to ask questions and to ask for help.

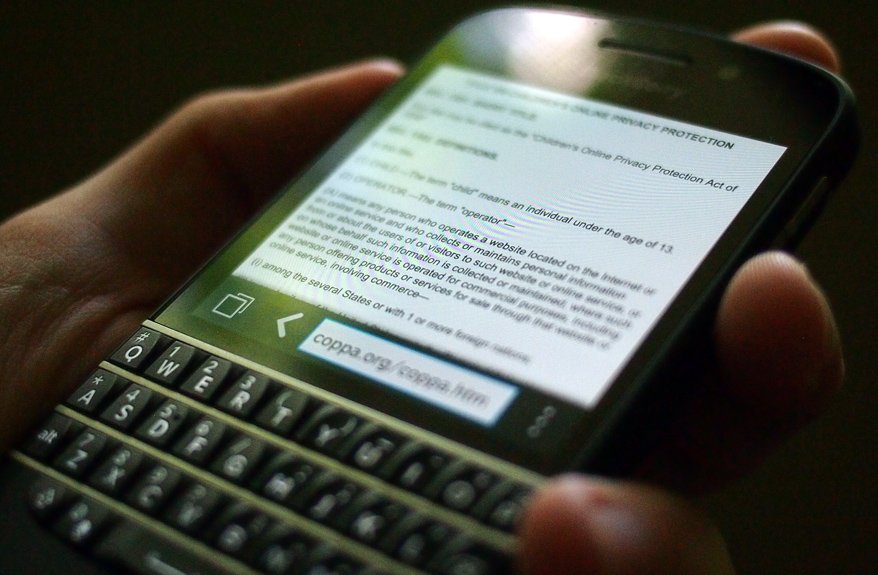

Title 15, United States Code, Chapter 91

Enacted by the United States Congress in 1998, the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act aimed to, as its name implies, protect children online. COPPA dictated what information must be included in a site's privacy policy, their responsibilities with regards to data collected about and marketing towards children under the age of 13, and how to verify ages. COPPA includes a provision for sites to allow users under 13 to give out their personal information with the authorization of a parent, but the verification process for that has proven too cumbersome for most sites.

A number of sites have been found to have failed to comply with the requirements of COPPA, including Lisa Frank, Mrs. Field's Cookies, and Hershey. In 2006, The Federal Trade Commission levied a fine of $1 million on the journaling website Xanga for repeatedly permitting users under 13 without parental consent. The FTC also fined UMG Recordings $400,000 for marketing towards younger children when promoting then-13-year-old pop star Lil' Romeo.

Privacy and personal security has to start with other basic Internet skills. Hell, it needs to be the No. 2 item on any how-to list, right after "Press the power button."

Parents and guardians are only part of the battle. Teaching online safety and security has to be part of school curriculum as well. And in a growing number of schools, it is. That doesn't mean parents can give up the responsibility of making sure our children know when it's OK to share, and when some things need to stay private. But we gladly welcome the help.

One of the most important things for us to do is monitor what our kids are doing and where they're doing it.

- Georgia / Therapist, Host of ZEN & TECH

Q:

Who is responsible for protecting children online?

876 comments

Conclusion

With everything we keep on and do on our mobile devices, keeping it all secure can be a struggle - mentally and physically. Understanding the threats that exist on the internet and how to avoid them, is an evolving challenge. Grappling with securing our devices, data, and accounts is also a challenge.

The most important aspect is physical security. All bets are off if you lose control. A determined and knowledgeable individual can circumvent nearly any software lock. But a simple PIN or pattern lock can deter more basic shenanigans.

Two-factor authentication provides another layer of security - more layers being better - but each layer introduces additional complexity and failure points. We don't want security so intense that it blocks us from our own devices. Perhaps biometrics will fill that role, providing near-infallible authentication, but not today.

Our children have to be raised with the same healthy fear and respect of the internet as they are of strangers and dark alleys. Most people on the internet are inherently good, but there are enough who will do us harm without a second thought.

When you think about it, the internet can be a scary place. Just how do we stay in the clear when the nastiness is lurking around the next hyperlink?