Pushing buttons vs. Tapping pixels: The great keyboard debate - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Social

Pushing buttons vs. Tapping pixels: The great keyboard debate

If you're reading this on a desktop or laptop computer, more likely than not there's a hardware keyboard sitting between you and the screen. If you're reading this on a smartphone or tablet, chances are there's not a hardware keyboard within the reach of your fingers. There was a time when hardware keyboards dominated the smartphone landscape, but in recent years they've been all but pushed out of contention.

What happened? Can we lay the blame entirely at the iPhone's feet? The first Android devices had physical and virtual keyboards, and Windows Phone launched with hardware keyboards in the mix. But browse the shelves at your local smartphone retailer and you'll find but a handful of hardware keyboards in the see of glass-fronted slabs.

So why is the hardware keyboard still around at all? What does it take to make a good one, and why won't people leave it behind? Are virtual keyboards not yet good enough, or are they just some level of refinement away from capturing the last hold-outs?

The keyboard is our primary data entry system on smartphones - it has to be good. And it can always be better - but how?

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Let's get the conversation started!

By Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson & Rene Ritchie

Play

Keyboards

Keyboards

- Hardware keyboards

- Video: Marcus Adolfsson

- Perfecting hardware

- Keyboard size

- Video: Vivek Bhardwaj

- Virtual keyboards

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Rene Ritchie iMore

Hardware keyboards aren't dead ... yet

Multitouch changed that. With the iPhone Apple eschewed the popular BlackBerry and Palm Treo-style keyboards of the time and went with a virtual keyboard that tried to make up for the lack of tactility with smarts built into the software.

A new generation is coming to mobile never having used a handset with a hardware keyboard.

For people who were raised on good, old-fashioned keyboards, it was a deal-breaker. For others it was good enough, and having a full-size screen more than made up for losing the tiny buttons. Over the last 6 years, Android's moved away from the physical keyboard as has Windows Phone, and even BlackBerry has launched several virtual-only devices. A new generation is coming to mobile never having used a handset with a hardware keyboard. Even some staunch keyboard fanatics have come to appreciate the advantages a full screen provides.

But for some, a hardware keyboard is and will remain the most important thing on the phone. Simon Sage, Mobile Nations' editor-at-very-large, clung to his BlackBerry 9900 well after it grew long in the tooth, waiting for the BlackBerry Q10 to replace it. He wants a keyboard, and he's not alone in wanting one.

QWERTYUIOP

Popular legend holds that the QWERTY keyboard layout was created in the early days of the typewriter to slow down young office secretaries. Supposedly they had grown so proficient that their speed was causing the arms of the typewriter to get caught up on each other, wrecking the machines.

That's not the truth, however. It is true that QWERTY came to be in the early years of the typewriter, but it was actually guided by the needs of telegraph operators. Early typewriters had an alphabetical keyboard layout, which the operators found inefficient for their duties in transcribing Morse code messages onto paper. They worked with the typewriter manufacturers of the time and the layouts changed many times before eventually settling on QWERTY in 1882. QWERTY has since become the dominant English language keyboard layout for more than 130 years.

That market likely isn't growing. It may even be shrinking. But it's there. It's not there for iPhone. It tried but failed to be more than a niche for Android or Windows Phone after being a dominant input method for Windows Mobile. But the physical keyboard has always been there for BlackBerry, and will be for the for the foreseeable future.

No one is fighting BlackBerry for the keyboard market, not any more, and what it means five or ten years down the road when natural language voice interfaces, currently embodied by Siri and Google Now, become even more advanced is unclear.

For Apple, for Google, for Microsoft, and maybe even for a large part of BlackBerry's product lineup going forward, the hardware keyboard is all but done. But it's not over, it's not done, until that traditional, die-hard, swollen thumbed, keyboard addict market is done.

I would really like to have a dedicated answer and hang-up button; call me old-fashioned.

- Marcus Adolfsson Founder and CEO, Mobile Nations

Q:

What type of keyboard do you prefer and why?

313

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

Tactile feedback, smiles, and the perfect hardware keyboard

Science can teach us a lot about what it takes to build a great hardware keyboard. Companies like BlackBerry and Palm spent years researching, testing, and refining to build the best mobile keyboards, focusing on building something more functional than flashy (looking at you and your laser-cut keyboard, Motorola Droid 4).

When it comes to desktop keyboards, the traditional QWERTY layout has standardized around 11 inches wide by 4 inches tall. It's been designed to the restrictions of the average human hand, whereas mobile hardware keyboards face significantly different constraints. They must factor in the size of the device, weight, durability, power, and even style.

Stainless steel dome switches

When it comes to hardware smartphone keyboards, there's really only one technology that's stood the test of time: dome switches. The keyboard is assembled in three layers: the keys (sometimes separated into two layers - caps and sub-keys), dome switches, and the circuits.

The circuits layer is composed of an array of open circuits, each placed directly under a key. The dome switch layer is made of a thin layer of stainless steel with conductive coating, or polymer with a layer of graphite on the inside of the dome. When the key above is pressed, it collapses the dome onto the circuits layer and bridges the open circuit.

Polymer dome layers are cheaper and quieter than metal ones, but they're also less durable and not as crisply responsive. Metal dome layers are typically reliable to over 5 million presses - far more than the average smartphone keyboard will endure.

In mobile we've seen manufacturers try all manner of strategies for hardware typing. Research in Motion and Palm established a rich history with their BlackBerry and Treo lines. But HTC, Motorola, Samsung, Nokia, and many others have experimented with hardware keyboards. They've had hard keys and gummy keys, straight rows and curved 'smile' layouts, clicky or quiet, portrait and landscape sliders, keyboards bisected by screens and rolled into nontraditional layouts. You name it, it's been tried.

Ultimately, the smile layout - where the rows turn upwards towards the edges of the keyboard - seems to have won the most praises, as have hard keys. Candy bar style or sliders are still a matter of preference, and each offers advantages over the other. Tactile feedback is of course important - users want a solid click and travel to mentally inform them that their key press was successful.

Keyboards are kind of like toothbrushes. We know the fundamentals, but can we improve upon it?

The problem with keyboards is they're kind of like toothbrushes. We know the fundamentals inside and out, so how do we make it better? Can slight variations make it even better? If a company prides themselves on their hardware keyboards (see: BlackBerry, Palm), then an enormous amount of research and development goes into refining the ideal design. Other companies who placed less emphasis on ergonomics failed (see: Samsung, Motorola).

In 2013, the question may ultimately be moot thanks to the relegation of hardware keyboards to a niche market. Now the focus is on how to perfect the virtual keyboard, including improvements on efficiency. The flexibility and updatability software means that a lot more creativity that can be used to solve these problems, which is quite fascinating.

Q:

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile social communications

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Bigger keyboards aren't necessarily better keyboards

Keyboard size matters. There, I said it! But, when it comes to typing on mobile devices, biggest isn't the best. A great typing experience is all about finding the sweet spot, the perfect size and mechanism that allows for speed, accuracy, and comfort, and ideally, both one- and two-handed use.

If the keyboard is too small, everything is cramped and accuracy really suffers. Too big, and you start to waste time traveling between keys. The perfect keyboard is big enough to allow for accuracy, but small enough that you're not wasting any time. It lets you get into a real rhythm -- it lets you dance.

The perfect keyboard lets you get into a real rhythm — it lets you dance.

Not all hands are the same size, of course, so manufacturers have to aim for the average. Smaller phones might appeal to people with tiny hands, and bigger phones to people with huge hands. For the majority of people, there's a wide range of options to explore.

Apple designed the iPhone for one-handed use. That's why even with the iPhone 5 when they increased the screen size from 3.5 to 4-inches, they did so by making it taller, not wide. Any wider and all of a sudden it gets much more difficult (for most people) to reach across to the far side of the device. It's still a tight keyboard when you try and type with two thumbs, however.

The body electric

The modern touchscreen was ushered into popularity with the original iPhone in 2007. The glass display sandwiched a mutual capacitive sensing layer that was used to permit multi-finger touch sensing.

Mutual capacitive touch screens use an array of miniature capacitors with a layer of glass etched with a microscopic conductive grid. A current is applied to the grid, which is disrupted when a conductive material - like your finger (the human body's electrical resistance varies, but is typically in the thousands of Ohms, while common electronics components gold, copper, and silver have resistance of less than 1/10,000,000th of an Ohm). The array of capacitors coupled with the grid can accurately pinpoint the location of multiple fingers on the glass surface.

By ramping up the voltage applied to the capacitive layer, touchscreens can be made sensitive enough to pick up the disruptions imparted by fingers even through layers of non-conductive fabric.

BlackBerry as a company built its reputation on making the best smartphone keyboards. It's something they are fanatical about, the way Google is for internet services and Apple is for design. BlackBerry users are historically two thumb typers, and over the years BlackBerry has found the sweet spot for the size of the phone that fits that style of two thumb typing. Even when making the Z10 with its new BlackBerry 10 touchscreen keyboard, they set the screen size at 4.2", allowing for easy one-handed typing, yet still being big enough for fast two-thumb typing.

Once you go beyond 4.2", with phones like the Samsung Galaxy Note II or LG Optimus G Pro, it just becomes too big for fast, rhythmic typing. Those screens might be great for gaming, watching video, sketching, and a bunch of other things, but not for keyboards.

When it comes to keyboards, it's not about being too big or too small. It's about being just right.

I've always been a die-hard physical keyboard fan.

- Vivek Bhardwaj Head of Software Portfolio, BlackBerry

Q:

Which phones are too big for your hands? Which are too small?

313

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Predictively typing our way to better virtual keyboards

Somewhere, deep in a cave in some forgotten underworld, lies the secret formula to creating the perfect virtual keyboard. The right mix of sensitivity and predictive text combined with the perfect visual skin and just the right number of buttons.

Today, however, we continue to seek out the virtual keyboard that's "good enough." And that's not to say there aren't some really good ones out there.

Apple didn't create the virtual keyboard, but in iOS it made the first one that didn't make us want to throw the phone against the wall. That's in part because of a generational shift in hardware as resistive touchscreens finally were replaced by multitouch capacitive screens, allowing a much lighter touch and much better responsiveness. But Apple's keyboard is a pretty no-frills deal — not even allowing for long-pressing for numbers of punctuation or symbols, offering minimal predictive options and customizability.

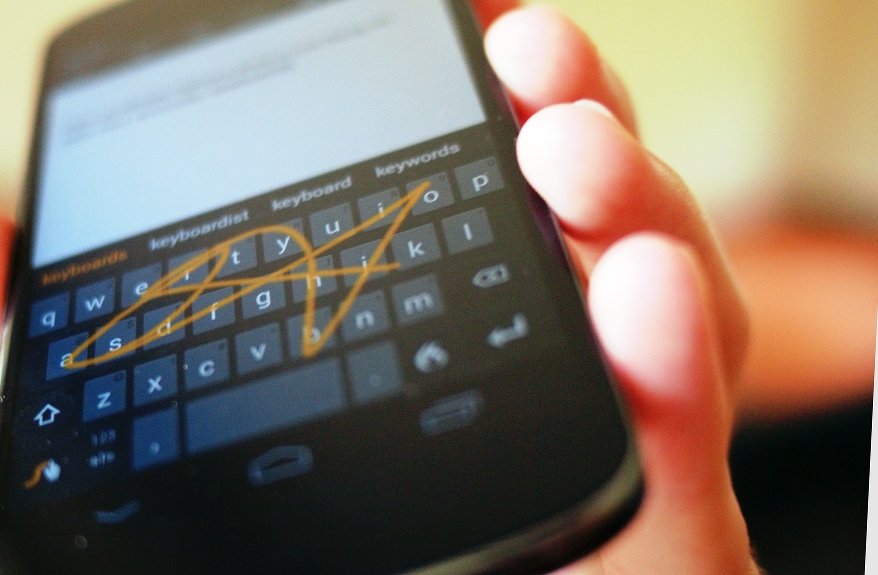

Swyped

One of the most popular third-party Android keyboards is Swype. For the first few years of its existence, Swype was only available only through a private beta program or preinstalled on specific devices. For two years, Swype continued on this road, shipping preinstalled on over 100 million Android smartphones. In April 2013, Swype finally exited beta status and became available to all compatible on Google Play. With widespread availability, Swype has been installed by more than 500 million users,

Unlike a traditional typing keyboard, Swype works by allowing users to continuously swipe their finger across the keyboard, hitting the letters in the word they're trying to type. Using analytical and predictive algorithms, Swype can determine with surprising accuracy the text being entered. Swype was acquired in 2011 by speech recognition company Nuance for more than $100 million.

Since Apple showed us it was possible to have a better-than-just-OK keyboard we've seen vast improvements on all the major mobile platforms. There have been some misses as well, I'm going to call out the SurePress clicking screen abomination that was the BlackBerry Storm, which was surely a sin against the smartphone gods.

So what makes a great virtual keyboard? It's any number of things. Responsiveness, for sure. And a proper layout. And predictive text. A dash of natural language processing (that's a big term you're going to hear more about in the near future). More options might not always be the best route, but some are better than none.

Things must work in concert to provide the best keyboard experience possible.

These things must work in concert to provide the best keyboard experience possible. And they must work well on any number of devices, from phones to tablets. It's no small feat.

Not every platform lets you choose your keyboard, and that's a shame. But at the same time it forces that platform owner to continuously improve its keyboard (and to keep from breaking what it already has), and that's a good thing as well.

Q:

Are you satisfied with how your phone predicts text input?

313

Conclusion

Hardware keyboards aren't dead, and for many manufacturers and platforms it would be fair to describe them as being on life support. While a few companies were serious and dedicated in their hardware keyboard building efforts, others approached the market with little more than a casual interest, and the results showed. The more buttons a user is required to interact with on a device, the better those buttons must be. Hardware keyboards can't be just "OK", they have to be great.

Today hardware keyboards are a breed relegated to niche status. The virtual keyboard has taken a massive and insurmountable lead, and that's not a bad thing. Billions of users have grown accustomed to typing on a glass capacitive touch screen and are no worse for wear. Virtual keyboards can be updated on the fly, can change their layout for different purposes, be swapped out all together, and dismissed for viewing the entire screen when not needed. They might not offer the tactility of a hardware keyboard, but they're far more flexible.

Picking a keyboard style is a matter of personal preference. If you want a hardware keyboard, there are certainly options available. If you prefer typing on glass, there are plenty of options there too. The best solution? That's entirely up to you.