Mobile music, podcasting, and the agony of VoIP - Talk Mobile

Presented by BlackBerry

Talk Mobile Creativity

Mobile music, podcasting, and the agony of VoIP

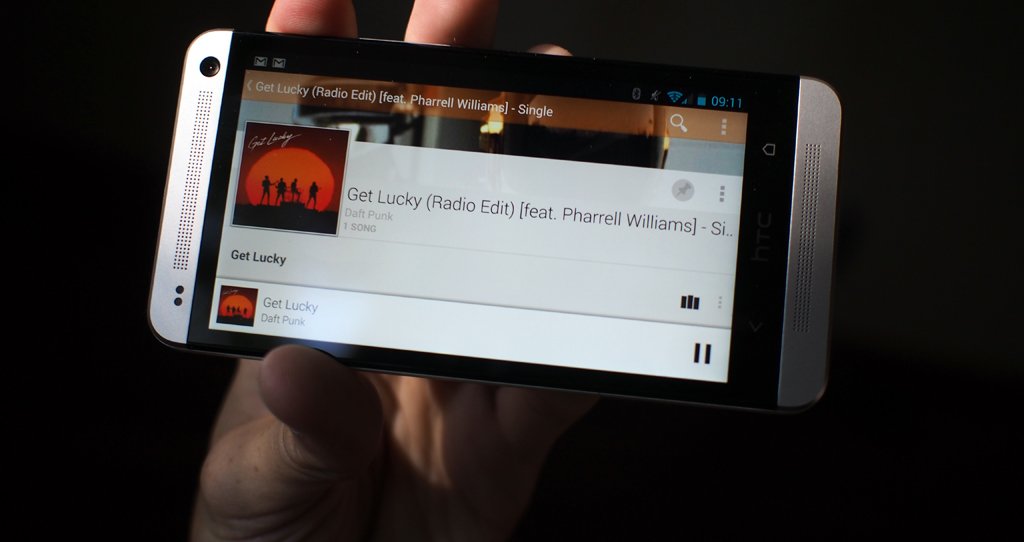

Your typical smartphone has two speakers. One is an earpiece for the phone part (it does make calls, right?), the other a loud speaker for speakerphone (there's that phone again…), music, games, and the like. A few handsets, like the HTC One, along with a handful of tablets, sport stereo loudspeakers, but by and large we're still only looking at two speakers.

These speakers carry the duty of all audio communication coming from our phones, unless you plug in some headphones or hook up an external speaker, that is. But even then, that's still audio coming from your phone. Our screens are important communications components for our phones, but just as important can be the speakers.

So why, does it seem, so often that what's coming out of them isn't so great? Are our VoIP protocols to blame? Or is it just mobile? Are the microphones and software available good enough for real podcasting? And does mobile have place on the theater stage or in the DJ booth?

Let's get the conversation started!

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

by Rene Ritchie, Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, and Phil Nickinson

Audio

Articles navigation

Phil Nickinson Android Central

VoIP: held prisoner by silos and preconceptions

The funny thing about VoIP — that's "Voice over Internet Protocol" — is that it's the wave of the future, one way or another. We'll start to see our first all-LTE phones in 2014. That is, phones that do voice and data over LTE, and not the old traditional methods. And that means all VoIP, all the time.

Sky Peer-to-Peer

Though not the first VoIP service, as in many industries that came before it, Skype was built with lessons learned from the mistakes of its predecessors. Launched in 2003 by a quartet of Estonia, Swedish, and Dutch developers, Skype slowly rose to prominence in the VoIP space.

So tempting was Skype that it was purchased by eBay in 2005 for $2.5 billion in cash and stock. eBay lacked a clear plan for what they intended to do with Skype, initially thinking to use it to link the auction service's sellers and buyers, but that integration never happened. Four years after purchasing Skype, eBay sold two thirds of the services to a pair of private equity firms for $1.9 billion. Microsoft purchased Skype in 2011 for $8.5 billion and used the service as a replacement for Windows Live Messenger.

Skype's rise came through their cheap rates for international calling. In 2005, Skype accounted for 2.9% of international calls; by 2012 that number had risen to 34%. Skype's entrance into mobile with the release of apps for iPhone and Android accelerated usages, setting records of more than 50 million simultaneous users online at once.

In the traditional sense, though, VoIP still kinda sucks. That's partly because the technology still struggles over mobile. Skype's come a long way. Google Hangouts are starting to come into their own. Apple's adding voice-only FaceTime in iOS 7. Even Facebook has toyed with calls through its own service. But VoIP in its current implementation needs a steady, consistent data stream. Latency on calls just isn't acceptable. Call quality itself has to improve. Those are major issue for mobile networks, especially here in the U.S.

These technical hurdles can and will be overcome. The larger battle will be waged in our own heads.

Then there's the issue of the apps themselves. No matter how great FaceTime, Skype or Hangouts may be, as services they're still prisoners of their own ecosystems, siloed in their own apps. That's not to say there isn't some cross-platform compatibility — Skype and Hangouts are two examples. But the excellent FaceTime never achieved the open nature that Apple once claimed it would.

The good news is that these are technical hurdles. They can and will be overcome. The larger battle will be waged in our own heads. Using Skype to make a traditional "phone call" is still a novel endeavor for many. Partly because of the reasons noted above, but also because you we're used to using our "phone" app to make "phone calls," and VoIP apps are used for other communication.

That will change. At some point someone will navigate the communication straits and truly make reaching out and touching someone as easy as the Bells of old imagined.

How often do you use VoIP calling?

876 comments

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

A future of mobile music creation

The first musical instruments were likely our own bodies, as our distant ancestors discovered rhythm and the sounds they could make by slapping the legs, abdomens, and each other. This led to rocks and sticks, and then stretched furs and taut bow strings. We blew into reeds and made sound, we blew into hollowed-out horns and made more noise.

Eventually we began to make purpose-built musical instruments, real drums and stringed instruments, primitive flutes and horns. As our skills and understand evolved so did our techniques, until we settled on a wide set of musical instruments, ranging from pianos, tympani, and guitars to saxophones, trombones, and didgeridoos.

Mobile's first steps into music creation were timid. They looked like miniature pianos confined to a smartphone's screen.

The advent of digital began to change things. Electric guitars rose up in the early 1930's and electronic pianos went public in the 1950's. The introduction of these electronic instruments revolutionized music, influencing jazz, giving birth to rock and roll, and defining modern music. Electronics even began to be applied to vocals with the 1997 introduction of Auto-Tune software.

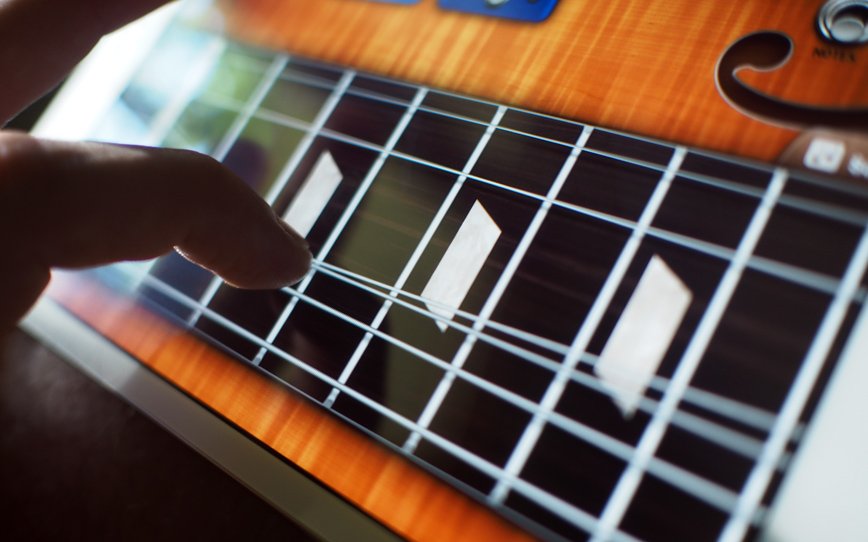

Mobile's first steps into music creation were timid. They looked like miniature pianos confined to a smartphone's screen, or a flat ocarina that responded to your touch and your blowing into the microphone. It was more toying around than serious musical creation.

Multitracking

Technically-speaking, the first multitrack recordings were stereo recordings, separating the left and right channels into separate yet concurrent tracks. Multitrack as we know it today - recording divided vocal and instrumental (and subdivided among that) tracks of a single piece - came into being in 1957 with the creation of the Ampex 8-track recorder (no, not that 8-track).

Multitrack recording rapidly revolutionized the creation of music. Prior to its introduction, performances for recording had to be done in their entirety, will all musicians involved performing together. With multitrack recording introduced, performances could be recorded separately, allowing for the creation of music with unprecedented complexity from smaller groups, as well as fine-tuning individual tracks without affecting the rest of the recording.

Multitrack recording eventually went digital, and today is bundled in Apple's GarageBand software. Not only can GarageBand users create compositions one track at a time, but multiple iOS device users can pair up to record a multitrack recording with their paired devices.

Things were slow to develop, at least they were until Apple brought their GarageBand music creation app from the Mac to the iPad in 2011. GarageBand brought together high quality sampling, multitrack recording, and an intuitive touch interface. As many have demonstrated with their own YouTube videos, it's fully possible to use GarageBand on an iPad to multitrack together your own recordings into an impressive final product - all produced on a mobile device.

That said, people aren't lining up just yet to see a guy on a stage make music with an iPad. As impressive as mobile music creation can be, it's impressive because it was made with a mobile device, not necessarily because it it's impressive music. That's not to say it's not possible, but it's worth noting that the first electric guitars and electronic pianos weren't much to right home about either, outside of their novelty status.

These things take time. Mobile devices and apps will find a place in music creation eventually. You can do a lot with a guitar or trumpet - but a tablet, that can make just about any sound.

I'm a musician. If you'd asked me five years ago if mobile could be an instrument, I would have laughed.

- Derek Kessler / Managing Editor, Mobile Nations

How do you listen to music with your mobile device?

876 comments

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

From turntable to iPod to tablets - say hello to the mobile DJ

Music and digital have been going together ever since Herbie Hannock's 1983 Future Shock (and Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk before). The idea of using technology like MIDI, computers, keyboard and sampling has grown steadily over the last 30 years and it's not going away.

Does mobile have a play in this field? Perhaps, though it still seems rather isolated. Some particular pragmatic uses of a smartphone is an instant-recorder for sound sampling, allowing a musician to record an interesting auditory experience nearly instantly to savor for later.

Another popular use is of "mix" apps where a stash of sounds, samples, beats and mixes allows even lay people to create their own club hits. Post to Facebook and share on SoundCloud, you could just be the next big thing.

Something feels fake about using an iPod to DJ, though you still need a musical ear to rock the party.

No doubt the biggest change has been seeing the prevalence of iPods and digital turntables, something that we've all experienced at clubs. By using the vast library of music stored on the iPod along with a few mixers and faders, DJs can now leave the vinyl at home and just go digital. Of course, something feels a tad fake about using an iPod to DJ, though there's no doubt you still need a musical ear to rock the party.

Aerial vibrations

The earliest smartphones contained traditional electromagnet-driven speakers, though once miniaturization became a concern the bulk of these speakers led to a switch to piezo-electric speakers, at least for the phone earpiece. Piezo speakers work by applying a current to a crystal such as quartz or barium titanate, the current induces flex and vibration, which is translated into a diaphragm form sound projection.

More recently phones have transitioned back to electromagnet speakers all around. These use a wire coil that is wrapped around a magnet that is fixed to the diaphragm. Applying current to the coil induces a magnet field that pushes away the magnet and thus the diaphragm. Either way, the vibration of the diaphragm causes compression waves in the air.

The advent of tablets is even starting to push into the space occupied by those traditional turntables. Apps on multiple platforms have staked a claim in being an all-in-one DJ'ing machine, though more often than not they're replete with skeuomorphic representations of the turntables they seek to replace.

While smartphones will have a limited role in music creation in 2013 and going forward, there's little doubt that tablets are ideal for such an endeavor. While pretending to be a piano, playing samples or acting like a monitor, such devices have an interesting and important role to play. Let's see what artists can do with them.

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile creativity

Rene Ritchie iMore

Podcasting isn't easy, and mobile is even harder

Podcasting ain't easy. Sure, sounds like the whiniest of first world nerd problems, but it remains true. Skype, which is what most multi-location podcasters use, is one of the worst audio software ever made, except for everything else. Audio recording and hijacking software is only as reliable as the person picking the wrong source behind it, and editing a show can bring out both the best and worst in sound quality. Now you want to try handling all that while mobile?

I exaggerate, of course. A little. Maybe. Here's the thing: At home I have a high end XLR mic and a good quality compressor going into an 8-core Mac recording in full quality AIFF format, in an environment that's almost completely, quietly, under my control.

When recording while mobile I have either an all-in-one recorder, or a decent USB mic attached to a MacBook, or an iPad or iPhone. And I can be anywhere from a show floor to a bar to a hotel room. And it's hard. More than hard.

It's possible to record a podcast while mobile, certainly, you just have to work at it.

It's possible to record a podcast while mobile, certainly, you just have to work at it. You have to make sure you have as good a mic as is portable and powered, as good a piece of recording software as can run on the device or devices you have available, and as good an editing app as is possible on those devices.

Putting on the Beats

Beats Electronics was founded in 2006 by rap mogul Dr. Dre and music producer Jimmy Iovine, with the goal of producing high-quality audio gear. Dr. Dre advertised the firm's first gear, the Beats by Dr. Dre headphones, as letting you "hear what the artists hear, and listen to the music the way they should: the way I do."

Beats headphones are said to work best when paired with Beats-enabled music players. HP partnered with Beats in 2011 to offer Beats Audio-equipped desktop and laptop devices, as well as the HP TouchPad tablet. In 2011, HTC bought a majority stake in Beats and soon began integrating the tech into their smartphones.

The mojo behind Beats is both digital and physical. The digital part is a proprietary equalization, though admittedly that is something that can be easily duplicated. Physically, Beats Audio devices are built to have an isolated audio circuitry, a discrete headphone amplifier, separate left, right, and ground wires, and special headphone jacks with limited grounding interference.

If you have guests, either with you on location, or at remote places all their own, you have to be able to record them as well, and in good enough quality to be usable.

It's a challenge, but it's getting better. USB mics are getting better, even the smaller ones. Lavaliers and hand mics are getting easier to use, even the wireless ones. And editing software is improving as well, even on mobile.

Nowadays you can podcast well from mobile, you just need to make sure you put in the effort to get it right. Because, podcasting ain't easy.

Mobile podcasting is becoming easier and easier, thanks in no small part to accessory manufacturers

- Simon Sage / Editor-at-Large, Mobile Nations

Who makes the best smartphone speakers?

876 comments

Conclusion

The only thing really holding back better audio on mobile is our own imagination and capacity to code. We've seen in the past few years the power that these mobile devices with their touch interfaces can unleash.

If you'd asked us five years ago if something like GarageBand would even be remotely possible in the next decade, chances are we would have laughed. But instead the capabilities of mobile technology have grown by leaps and bounds, and show no sign of abating, short of our own ingenuity and originality in programming these devices.

It'll take time for mobile music to really come into its own. We're just starting to explore what's possible with mobile music creation and with mobile devices in the DJ's kit. Where these apps go from here isn't so much up to our own preconceived notions of music, but more the whims and creativity of the developer.

As with all things mobile, podcasting will become easier to pull off with mobile devices. Interactivity between apps and services is key in making this happen - a feature that mobile devices haven't yet as fully embraced as PCs.

Where do you see the future of mobile music and podcasting?