Carriers: picking the lesser of all evils - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Carriers

Carriers: picking the lesser of all evils

Talk Mobile 2013 has so far touched on the big rocks of devices, operating systems, and services. Now it's time to touch on the biggest and most expensive rock in the mobile device system: the carriers. Most of us get locked in to two or three year contracts that can add up to thousands of dollars over the life that contract.

Our choice of carrier determines so much. It sets not just the cost of our service, but the quality and extent of our service. The carriers can discriminate on what content we are served, who we call and at what rate, the third-party services we access, the devices we can use, and so much more.

With all of these variables, how are we supposed to pick a carrier? Should we let the device selection dictate our choices, or the service itself? Are there advantages to picking a smaller carrier over the big national brands? And what's our recourse if we're not satisfied with our choice?

There's a lot to discuss when it comes to carriers. Big and small, cheap and expensive, they're an important part of the mobile ecosystem.

Let's get the conversation started!

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

by Rene Ritchie, Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson

Carriers

Articles navigation

- Phone or carrier?

- Video: Derek Kessler

- Picking a carrier

- Small carriers

- Switching carriers

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Pick your carrier, then your phone

That day is no longer. Today, flagship smartphones - the ones that people used to switch carriers for - regularly launch in one form on all or most carriers. There might be a staggered release where one carrier gets the first launch, but it's usually only a matter of weeks, or rarely months.

It doesn't matter how awesome your new smartphone is if it can't get a signal.

But even if we still lived in a time of carrier exclusives that lasted into eternity, our advice would still be the same: pick a carrier, and then pick a phone. It doesn't matter a lick how awesome your new smartphone is if it can't get a signal. Carriers like to brag about their coverage, and if you live in a major metro area you'll usually be okay when it comes to coverage.

Usually. Every carrier has dead spots, and that might be where you live, work, or party. If there's no signal, your fancy new smartphone is now a fancy new PDA, or paperweight, whichever strikes you as the worse fate for top-rate modern electronics.

Subsidize this

The overwhelming majority of customers on the major carriers in North American and Europe buy their mobile phones on a contracted plan, subsidizing the cost of the phone over the life of the contract. This allows for the customer to buy an expensive phone - like a $599 HTC One - for much less up front, rarely more than $199 for a base model (in this case a 32GB model on AT&T). The remainder of the cost of the phone is spread out over the two-year life of the contract.

Typically, about $20 per month goes towards the subsidy, and the average subsidy is right around $400. After around twenty months, the phone is completely paid off, but on most carriers there's no reduction in the cost of service - the carrier continues to collect the $20 subsidy charge (which for obvious reasons isn't broken out on bills). Even worse is when a customer brings their own device and isn't offered reduced pricing thanks to the lack of subsidy.

The German carrier model for years has decoupled the phone from the service, and once the phone is paid off you stop paying for it. T-Mobile has brought that system to the United States, though so far is alone in decoupling implementation in North America.

Fortunately, with few exceptions every major phone comes on every major carrier, and even many smaller regional and national networks. There are several factors we can thank for that, including the rise in demand for specific smartphone models and the corresponding rise in power of those manufacturers. Apple and Samsung are powerful enough today that they can offer the same phone to every carrier, no modifications, no exceptions. Even BlackBerry and HTC are able to get away with putting the same phone on multiple carriers.

There are exceptions - With few exceptions can you find the same exact Nokia Lumia smartphone on multiple carriers, and HTC and Samsung aren't above carrier exclusives for their non-flagship devices. But generally those are small differences, such as a body shape, camera quality, or screen size.

Pick your carrier, then pick your phone. It's the only way.

It doesn't matter how awesome your phone is if you can't get a signal.

- Derek Kessler / Managing Editor, Mobile Nations

Q

Should you pick your phone or your carrier first?

876 comments

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Coverage, coverage, coverage

Now that we've all agreed we should pick carriers before picking phones, it's time to let you in on a little secret. That's the most difficult way to go about it. Phones are sexy. They're tangible. You can look at pictures, read reviews, go to a store and hold one in your hand. They're mostly variable-free. What you see is what you get.

Carriers and coverage are a little more tricky. But at the end of the day, what good is the world's best phone, the one for which you suffered through week after week and finally shelled out hundreds of hard-earned dollars for, if you can't get data or make calls?

While lab testing is important, real-world results are what's important to the rest of us.

This is something we struggle with every day as editors, when readers ask the inevitable "Yeah, but how's the reception?" question. What's good for us, where we live, may be bad for you, where you live. While laboratory testing is important for obvious reasons, real-world results are what's important to the other 99 percent of us.

The good news is that there are tools available to help navigate this minefield.

Before you buy anything, ask your friends and family. We can't promise that you'll get a technical, educated answer, but at the very least you should get some anecdotal ideas of which carriers have good coverage where you live and work.

Secondly, make sure you look over the coverage maps for the carriers in your area. If LTE data is a necessity, make sure it's actually an option where you'll be using your phone the most. We'd treat carrier maps as blunt instruments and not precision roadmaps, but they're a must when choosing a carrier.

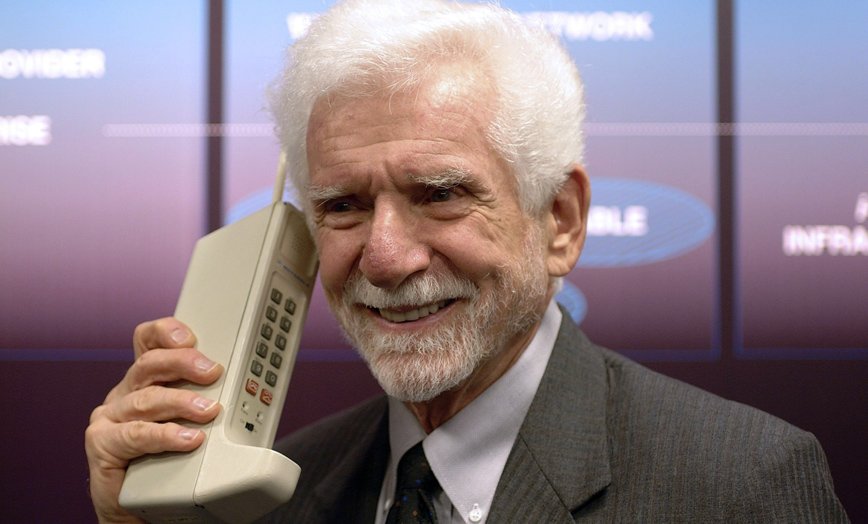

Advanced Mobile Phone System

Though radio-based mobile phones had existed since the late 1940s (as 70-pound units, so "mobile" was relative), the first true cellular network was launched in 1978 by Bell Labs. The analog system was named Advanced Mobile Phone System, or AMPS. Several carriers in the North America , Israel, and Australia operated AMPS networks.

What differentiated AMPS from the radio-based networks that preceded it was flexible tower and frequency assignments, permitting a much greater number of devices to be connected at one time in an area. As an analog signal, though, AMPS was susceptible to static and interference, as well as eavesdropping and spoofing that led to the first real security measures for mobile - PINs for placing calls and radio-frequency identification.

Despite its age, AMPS networks were operated for decades around the globe, in part thanks to its robust service area. In 2005, Alltell reported that a full 15% of their subscribers were still using AMPS. Non-phone services like OnStar vehicle communications and security, ADT home security relied heavily on AMPS networks. Carriers in the US and Canada operated AMPS networks through 2008.

Image source: WirtshaftsBlatt.at

There are several apps that crowdsource network coverage. This is as real-world as you can get. You load an app onto your phone, and it runs in the background, reporting back signal strength and other coverage data for wherever you take the phone. Sensorly is one. RootMetrics is another.

And remember that you have options. All carriers have a grace period for returning phones and getting out of contracts. But you need to know just how long that window is — and they've grown significantly shorter over the years.

Q

How did you decide on your carrier?

876 comments

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

Small vs. large, regional vs. MVNO

In 2013, the debate between which is better — large or small carriers — is increasingly becoming less of an issue. With the constant mergers and acquisitions of regional partners, you don't have to look far to see that carriers (e.g. AT&T) have reconstituted themselves as giants decades after being broken apart for being just too big.

Still, there are plenty of smaller carriers around. They exist in three forms: the regional carrier that has a local coverage area and roaming elsewhere (Cincinnati Bell Wireless, Alaska Communications, and Cellular One), smaller national carriers (Cricket Wireless and U.S. Cellular), and a growing brood of MVNOs - mobile virtual network operators, i.e. companies that lease wholesale bandwidth from a major national network (Virgin Mobile, Aio Wireless, and Straight Talk). They can offer some surprising deals for customers, from unique features to savings in service and devices.

Mobile Virtual Network Operator

A Mobile Virtual Network Operator - or MVNO - is a wireless service provider that actually doesn't own the network itself. An MVNO leases wholesale bandwidth from an actual mobile network operator and resells that access to its own customers. Typically a MVNO will have its own customer service departments, storefronts, and billing systems, and marketing. By buying network space wholesale and offering lower cost devices, the MVNO usually can pass significant savings on to customers.

The first true MVNO launched in 1999 in the United Kingdom. Virgin Mobile leased network space from T-Mobile UK (now EE) as part of a partnership with Virgin Group. The MVNO's success was duplicated three years later in the Untied States, this time leasing bandwidth from Sprint. Specialized MVNOs begin to crop up, such as ESPN Mobile for sports fans and Disney Mobile for families, though for years it seemed such ventures were doomed to failure.

Arguably one of the most successful MVNOs is Straight Talk, a partnership between TracFone (itself a MVNO) and retailer Wal-Mart. Straight Talk offers devices that operate on all four major US networks and plans as low as $30 a month - though that's for 1000 minutes of talk, 1000 texts, and 30MB of data.

They do it by not competing against the big carriers for exclusive, expensive high-end smartphones that need to be heavily subsidized. A lot of small carriers offer only low- to mid-range devices, and only get the flagship devices months after launching on other carriers.

That doesn't mean you can't bring your own device though, which is becoming an increasingly popular option for some consumers. It is certainly more expensive up-front to buy a $500 smart device, but with many carriers offering reduced monthly rates and or pay-as-you-go options, users may find it more advantageous than dealing with the larger carriers.

The determination of "value" often translates into "you get what you pay for".

Ultimately, the determination of "value" often translates into "you get what you pay for". For instance, AT&T and Verizon are arguably the most expensive carriers when compared to Sprint or T-Mobile, let alone the smaller MVNOs. But with AT&T and Verizon you also get access to top-tier devices and better network coverage and speeds (even over on-the-same-towers MVNOs). It's up to you to decide if the latest-and-greatest trumps cost.

Then again, one could make a strong argument for the smaller carriers in terms of customer satisfaction (or lack of frustration). The smaller companies know they have to work harder to keep you happy, whereas on AT&T and Verizon, you're just one of millions of customer. There's something still to be said about the more personal experience and attention you can get from a regional carrier. For some, it factors into the "value" equation and cannot be dismissed.

Q

Is the value proposition of smaller carriers enough for you to switch?

876 comments

Rene Ritchie iMore

The price you'll pay to switch

You walk into a carrier store with an old phone and emerge a few minutes later with the newest, hottest handset on the planet, faster and better in every way, and all for less than you've ever paid before.

Sounds nice, eh? It's my kind of dream. But we don't always get our dreams. And when it comes to the carriers, especially in North America, most of us get something more akin to nightmares.

We're not used to, and we don't want to, pay full price for a new phone.

We're not used to, and we don't want to, pay full price for a new phone. Or anything. Top-of-the-line handsets today cost $600 or more, and that's a lot of money up front. Just as we buy houses with mortgages, we buy phones with subsidized contracts. We pay a small amount up front, maybe nothing, maybe a couple hundred bucks, and we agree to keep paying the carrier for months and months to come.

A few years ago, once that happened, you were pretty much done. If you wanted to change carriers later, because your carrier treated you beyond badly, another carrier got an exclusive phone you just had to have, or you moved and wanted one with better service in your area, tough luck. Numbers weren't portable, so all your contacts would have to update or risk losing you. Early termination fees (ETF) were egregious, so you'd be out of pocket on your old contract before your new phone was anywhere near in pocket.

Some of that has changed. Number porting is certainly easier now. ETFs aren't really, especially with the big carriers. In some ways, fair enough. They let us take that expensive new phone on what was essentially an installment plan, and we need to finish the installments or buy it outright. But that should be the legal limits of the deal.

I moved, here's my new number…

In the earliest days of telephone service, phone numbers were tied to the address of the house. When phone service became more ubiquitous and numbers weren't the address, providers eventually offered number portability so a move across town wouldn't mean a whole new phone number. Number portability for landlines was mandated in the United States in 1997.

With the rise of wireless carriers, customers were presented with a new set of phone number challenges. For several years, many had both a home landline and cellular service, and while they could move out of town and take their cellular number with them, they couldn't switch carriers in town and transfer the number.

In 2003, the Federal Communications Commission mandated that wireless carriers would also have to support number portability, both between carriers and from landline services. That mandate was extended to VoIP telecommunications providers in 2007. Canada, South Africa, and the United States are the only countries where full number portability is offered.

Even when fairly applied, ETFs can be a barrier to exit for a single person with a single phone. For a family with several phones, it can be switch-breaker. That's especially true if only one family member wants to switch and you have discounts, shared minutes and data, in-network services, and other factors to consider.

While there's been some movement towards better customer service, especially by the smaller carriers like T-Mobile in the US (because they have to, let's make no mistake) the true cost of switching is still measured not only in money but in time, effort, and frustration.

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile clouds

Conclusion

For most of us, picking a carrier is a commitment. Not only are you committing to pay for service for the next 24-36 months, but you're committing to that service and, for many of us, committing to a single smartphone for that time as well. You might only be paying a few hundred dollars up front, if anything at all, but the costs really do add up over time.

That is, unless you go for the prepaid monthly plans, or opt into the device upgrade schemes the large carriers have rolled out. Or you purchase a device without a contract and go month-to-month for your service.

Regardless of which door you open, there are only a few smart routes to getting there. Firstly, you absolutely must pick your carrier before your device, and you can't pick your carrier on cost alone. If you don't get service, it doesn't matter which device you have, it's not going to do what you need it to do. From there, it's a wide world of carrier choices and device selections, contracted and uncontracted, full cost and subsidized.

It's up to you which door to open.