Can we end carrier exclusives and bloatware? - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Carriers

Can we end carrier exclusives and bloatware?

We will always advocate picking your carrier before picking your phone, but sometimes the allure of a specific phone can be too much to overcome. Millions switched to AT&T to get access to the first four iPhones, BlackBerry faithful jumped to Verizon and Vodafone to get the first BlackBerry Storm, and old Palm fans moved to Sprint to pick up a Palm Pre. They made these moves not out of interest in monthly savings or coverage, but for a specific device - one exclusive to that carrier.

These carrier exclusives have long been a fact of life in the smartphone space, but with smartphones becoming something that even the average consumer has an opinion on, they're increasingly becoming more of a headache. When it comes to smartphones, there's little worse than the new hotness landing on a different carrier than yours and you finding yourself a year away from getting out of your contract without forking over a heft ETF.

Exclusives can be good for manufacturers, no doubt. But can they be bad for them too? And are they bad for consumers outside of the frustration of denial? And what about all of the apps and services that the carrier insists on loading on these handsets - are they useful, or just useless bloat?

Just what are the carriers doing here, and what does it mean?

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Let's get the conversation started!

by Rene Ritchie, Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson

Carrier intervention

Articles navigation

- Exclusives pros and cons

- Carrier bloatware

- Video: Alex Dobie

- Ending exclusives

- From who are you buying?

- Video: Derek Kessler

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Carrier exclusives: Sometimes good, sometimes bad, often upsetting

Carrier exclusives can be good for manufacturers. While it may mean limiting the potential addressable market (sometimes only temporarily) to a single carrier in a nation, it also means that they're going to have the obscene marketing budget of that carrier lavished on their device. They'll have dedicated in-store displays, better training for the store's staff, and in exchange for having to make a device just for that carrier, they might even be able to argue less with the carrier over how much they're going to be paid.

This creates variety in the marketplace. Take Nokia as an example. AT&T has the polycarbonate Lumia 920, while T-Mobile got the Lumia metal-and-polycarbonate 925 with an improved camera. Verizon got another variant in the Lumia 928, with a squared-off polycarbonate body, improved camera, and xenon flash.

Exclusive not-the-iPhone

While carrier exclusives were nothing new when the iPhone landed in 2007, there's no denying that the phone's success reshaped consumer perceptions of smartphones and what they expected from carriers. The iPhone's exclusivity to AT&T created openings at the other US carriers, leading entrants on each seeking to compete.

First up was the HTC G1 a year later, the first Android smartphone and an exclusive to T-Mobile. While the G1 itself wasn't a rousing success - the hardware was clunky in comparison to the iPhone, and while the Android 1.0 operating system was more capable that iOS, it lacked mass appeal. Verizon and Research In Motion partnered to launch the first full touchscreen BlackBerry - the Storm - in 2008. It sold well, but was panned by the tech media for its clicking touchscreen.

Sprint took the longest to push out an exclusive competitor to the iPhone. The Palm Pre launched on the carrier on June 6, 2009, just two days before Apple's anticipated announcement of the iPhone 3GS. Of all the early attempts to combat the iPhone with an exclusive, only the G1 can be considered a success. It didn't sell well itself, but Android has gone on outsell iOS on a global scale.

That variety leads to expansive the "cons" column. Exclusives for different carriers increase device maker's manufacturing load. The Lumias 920, 925, and 928 are rather similar devices, but differences in screens, body, camera, etc mean that Nokia has sees increased complexities.

Samsung used to fall into that trap, exemplified best by the Galaxy S II. It was packaged in different shells with different screens on different carriers. Sprint even had a version with a slide-out physical keyboard. After the success of the varied S II line, Samsung had enough power to assert the S III as they made it on the carriers. Apple jumped straight to the power-over-the-carriers position; the only consideration they would make for carriers was compatible radios and bandwidth restrictions.

What if you want the Lumia 928, but you're on AT&T? Tough luck, you can't have it.

Exclusives suck the most for customers, though. What if you want the Lumia 928 with its thinner body and xenon flash, but you're on AT&T? Tough luck, you can't have it. But you can have a Lumia 1020 with its insane camera. But you can't have a Motorola Droid Maxx, because those belong only on Verizon.

Carrier exclusives limit customer choice, forcing us to choose a carrier by not just the quality and price of their service, but by their ability to manipulate manufacturers. That's not fair to anybody.

Q

Have you ever switched carriers for an exclusive device?

876 comments

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Bloatware is the bane of the smartphone nerd's existence

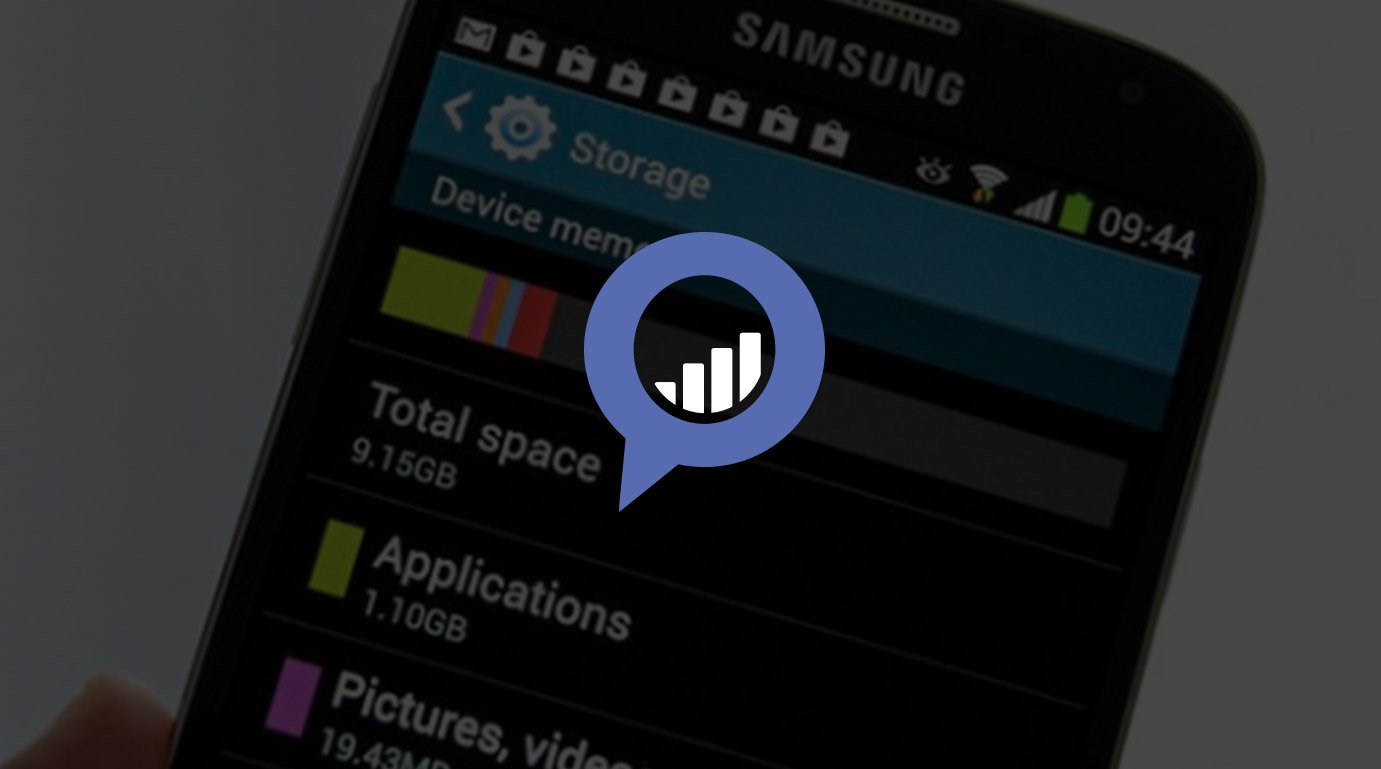

Ah, bloatware. The scourge of any self-respecting smartphone nerd. The definition of bloatware can vary a little bit. In the strictest sense, it's an app — any app — that's preloaded onto the phone by the operator and isn't native to the operating system. Maybe you find some of those apps useful. But they're still taking up room on your phone, and you didn't load them yourself.

And in many cases — and on Android phones in particular — these apps can be impossible to uninstall without hacking the phone.

Bloatware is evil. But it's also a method by which the operators can add additional functionality to a phone. And to make more money in the process.

Android, but not as you know it

The first Android phone, the HTC G1/Dream, ran Android 1.0 as Google intended it. The device was developed in conjunction with HTC, and produced before manufacturers and carriers realized the extent to which they could modify the open source operating system.

Today nearly every manufacturer of Android-powered devices ships their hardware with a modified version of the Android software. Some modifications are mild, like the alterations to the lock screen and Google Now voice triggers that Motorola made on the Moto X. Others are more comprehensive, touching nearly every aspect of the Android user experience, like Samsung's TouchWiz and HTC's Sense.

LG, Sony, Pantech, ZTE, Alcatel, Dell, Garmin, have all also offered Android smartphones with varying degrees of customization. Part of the drive to customization was driven by a desire for differentiation between manufacturers, but also as an attempt to pretty up the less-attractive pre-Duarte/Holo Android interface.

Bloatware's not a given, though. Apple had the bargaining power to keep the operators from preloading apps onto its phones and tablets. Microsoft allows it but keeps tighter a tight rein on things. BlackBerry 10 is pretty clean. Android is wide open and a freakin' mess. Hell, back in the day we saw the likes of Verizon strip out some Google services and replace them with Microsoft's - Bing search as a default on Android? That ain't right.

Most folks just put up with it. Out of sight, out of mind. Or maybe you find the apps useful. There's actually nothing wrong with that, never mind what the nerds tell you. The carrier apps usually aren't alone - sometimes there are manufacturer apps, or some useful apps you're likely to download anyway, like Netflix of Kindle.

If it bothers you enough, you can hack into your phone and start deleting apps.

If it bothers you enough, you can hack into your phone and start deleting apps. Or, on some platforms, you can load a custom ROM and start from scratch. Or, our favorite method is to vote with your wallet. Give money to an operator and manufacturer that doesn't load up your phone with apps you don't want, or go with one that at least makes it easy to remove the bloat.

But in the end, the platform owners have the best chance at protecting our sensibilities. They have to take control of their end product. Apple's done it. Microsoft is sort-of doing it, as has Samsung. The operators want their own little section of an app store to peddle their wares? Fine. But quit putting crap in our shopping carts.

There's nothing worse than buying a shiny new phone and finding it comes pre-loaded with all this crap you're never going to use.

- Alex Dobie / Managing Editor, Android Central

Q

Are you bothered by carrier apps or restrictions on your phone?

876 comments

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

How to bring about the end of carrier exclusives

In 2013, the division in hardware manufacturers is pretty stark. On one side, you have Apple and Samsung, who can seemingly snap their fingers to get all the networks on board with their "next big thing". And then there's everyone else.

Why the discrepancy? It all has to do with market power. As soon as one smartphone maker sells enough phones and amasses enough consumer recognition, they can push back against carrier control and demand what they want. The tables can be turned far enough such that it's the carriers that are the ones groveling at the manufacturer's feet - case in point: iPhone.

When you're not in a powerful position, you're at the will of the carrier.

Some manufacturers just have enough history with carriers that they can offer the devices they want, as BlackBerry and HTC can. But others, like LG and Nokia have to play by the carrier's rules. That can mean exclusive devices, sometimes with what some might view as alterations for the sake of alterations. When you're not in a powerful position, you're at the will of the carrier.

Of course, there's some benefit to the manufacturer in going along with the carrier's demand for an exclusive. They often get significant marketing support - think Verizon's Droid ad campaigns, Sprint's commercials featuring the Palm Pre, or AT&T advertising the Nokia Lumia 1020. Exclusive phones also get better store staff training, and even sometimes a better subsidy deal for the manufacturer. When you're the underdog, trading wider availability for an exclusive beats the "we'll put it on our shelves, but won't push it" alternative.

On any carrier, as long as it's AT&T

The original iPhone launched in 2007, exclusively on AT&T. That's not exclusively in the United States, but only on AT&T at all. A year later, the second generation iPhone - the iPhone 3G - launched. The 3G was still exclusive to AT&T in the USA, but globally landed on 26 other carriers in 20 other countries.

iPhone releases continued to follow a yearly schedule with the iPhone 3GS coming in 2009 and landing on 30 carriers. In 2010, Apple released their first SIM-unlocked version of the iPhone with the iPhone 4, allowing it to be used on any technically-compatible carrier, as well as partnering with even more carriers - but still remaining exclusive to AT&T in the United States. That changed in January of 2011 with the launch of an iPhone 4 made specifically for Verizon's CDMA network.

By the time Apple announced the iPhone 4S in October of that year, the iPhone was being carried on 200 carriers worldwide. The iPhone 5 in 2012 saw a launch on even more carriers, including dozens of smaller regional carriers around the globe.

So what can consumers do to change this? Well, ironically one option is for a device to become such a hit, the other carriers have to offer the same or similar device on their network just due to market pressure, as has been the case with the iPhone and Samsung's Galaxy S and Note lines.

Another option? People need to prepare to put their money where their mouth is. If your carrier doesn't offer the device you want, or has a history of being late on the hardware front, then you need to pack your things and go to another carrier that does (and still has service where you live, of course). You might have to trade-off data speeds of monthly costs, but perhaps what you are buying is a better selection.

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile clouds

Rene Ritchie iMore

You're buying a phone from three companies at once

Love Gmail and want a phone that offers more Google goodness? How about a Samsung? Or an HTC? Or an LG, a Sony, or a hundred variations from any of a dozen manufacturers? You can get an HTC One or Samsung Galaxy S4 running manufacturer-altered Android, or one with stock Android. Or there's a Nexus from Google (but built by LG) that runs stocker than stock Android.

Wait, that's complicated. You have a Samsung TV and want a Samsung phone. There's a Galaxy S4 that runs Android; but the TouchWiz version or the Google Play edition version? Or if you prefer Microsoft, there's one running Windows Phone 8. No? Okay, there's this Tizen thing that... nevermind.

Let's try again. You're on Verizon. They have Samsung's Galaxy, running Google's Android. They have their exclusive Droid line, also Android, but made by Motorola. They also have LG Android phones, Samsung and Nokia Windows Phones, and phones from Apple and BlackBerry – heard of them?

No, no, don't cry, these two are easier. Apple makes the iPhone and BlackBerry makes the Z10, Q10, and Q5. They both run their own software and are mostly the same on every carrier. Apple even has their own stores. Cool?

Sprinting towards… something

Sprint claims ancestry into the 1800s, with the 1899 formation of the Brown Telephone Company in Kansas. Brown eventually became United Utilities, and then United Telecom in 1972. In 1983 they began offering local cellular service under the TeleSpectrum brand.

In 1982, GTE merged with Southern Pacific Communications, taking SPC's Sprint phone service nationwide. The new GTE Sprint then merged with a trio on United Telecom properties in 1986, forming US Sprint. After two years, United Telecom sold Telespectrum to Centel to buy a majority stake in Sprint, which it wholly acquired in 1992. The next year, Sprint bough back Centel and its wireless service.

Sprint's first PCS cellular service launched in 1995, building on the CDMA standard. In 2004, Sprint and Nextel merged in a $36 billion deal; the technological and cultural complexities of the merger set the combined entity's technical and fiscal progress back for several years. By 2008, Sprint had written down $30 billion of the cost of the Nextel merger. Since the Nextel decable, Sprint has struggled to maintain profitability and its customer base, leading to an agreement in 2012 for Japanese telecom SoftBank to purchase 70% of Sprint for $20.1 billion.

Some companies, like Google and Microsoft, make software that runs phones - Android and Windows Phone, respectively. They license it to others that build phones. They don't really care which phone you buy, as long as it runs their software. You love their other software, you'll love them on phones, they swear!

Then there's Samsung, Nokia, HTC, LG, Sony, and a dozen others that build phones. They take that software, add in some a bundle of their own code, and then offer a bunch of phones. They don't care what software you run, as long as you buy their phone. Some make other stuff too, like refrigerators or consoles, and they think you'll love their phones.

At the end of the day they'd rather you buy any phone from them over any phone from another carrier.

Lastly, you have carriers like Verizon, Vodafone, T-Mobile, EE, Rogers, et al. They don't make diddly-squat, but they're often where you go to buy everyone else's stuff. They may prefer you buy one phone over another, depending on their profit margins, but at the end of the day they'd rather you buy any phone from them over any phone from another carrier. Also, you had your flip phone from them, and you loved that, right?

Why won't you stop screaming?

The smartphone buying experience is kind of weird - you're simultaneous buying from a carrier, a manufacturer, and a platform.

- Derek Kessler / Managing Editor, Mobile Nations

Q

Is your loyalty to the carrier, the manufacturer, or the software?

876 comments

Conclusion

There's no doubt that carrier exclusives are one of the great frustrations of smartphone enthusiasts. Of course, they're merely looking out for their own best competitive interests, and so long as the manufacturers are willing to play along - of have no choice but to - that's not going to change.

There are some manufacturers that have been able to get around the exclusives deal. Apple and Samsung have by sheer willpower. HTC and BlackBerry, which the networks want to carry, don't have the money to do the exclusives deal. Nokia's perfectly willing to play the exclusives game, offering slightly modified versions of the same device on three different carriers - but they can get away with it thanks to the line's comparatively inexpensive hardware.

Carrier exclusives have been great for some carriers (AT&T with the iPhone) and awful for some manufacturers (the Palm Pre on Sprint). But by and large they've been a pain for customers. If you pick your carrier by the quality of their coverage in your area, then you're limiting your device options.

For as much pain as exclusives have been, the likes of the iPhone, Galaxy S4, Q10, and One show signs of that trend abating. Are we on the cusp of greater cross-carrier availability, or is this just a blip on the exclusivity radar?