The most important announcements at MWC were also the most boring

The Fira Grand Via is a huge complex, stretching connecting halls interspersed by meeting spaces, outdoor cafes and a snaking walkway that rests above the main floor, an express route of sorts between the chaos of the ground.

Each year at Mobile World Congress, once the embargoed releases are over — a phenomenon seemingly happening earlier and earlier — the show floor opens, and the real work begins: tracking down the minor hits, the technologies that, in a year or five, will end up transforming your phone into even more of an essential device than it is today.

One such innovation comes in the form of a replacement — augmentation, in fact — of the traditional SIM card. See, SIM cards are antiquated. The idea of inserting a piece of plastic into a removable tray to facilitate the connection to a single carrier is just not user-friendly in the age of virtual networks. Indeed, the continued use of SIM cards is largely propagated by the carriers themselves, since they encourage lock-in, both domestically and abroad. You use their network at home, and pay them to connect to a preferred roaming network abroad. It's a win-win for them, and potentially a total loss for the customer.

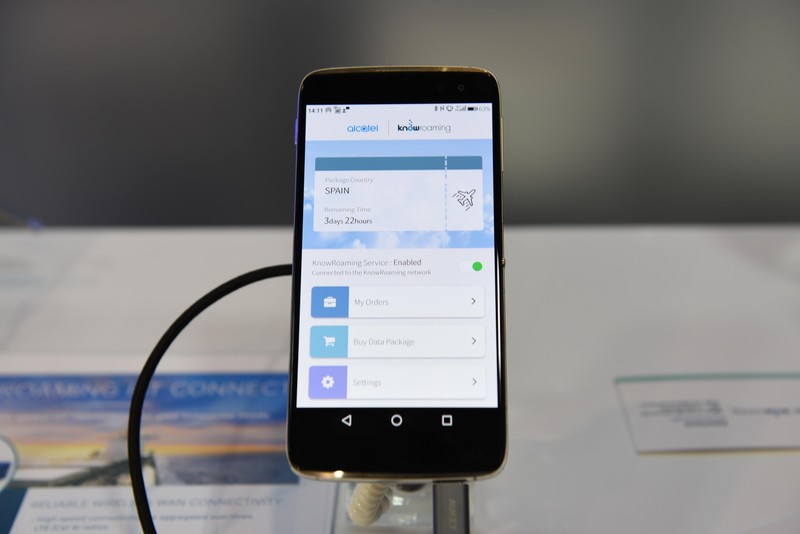

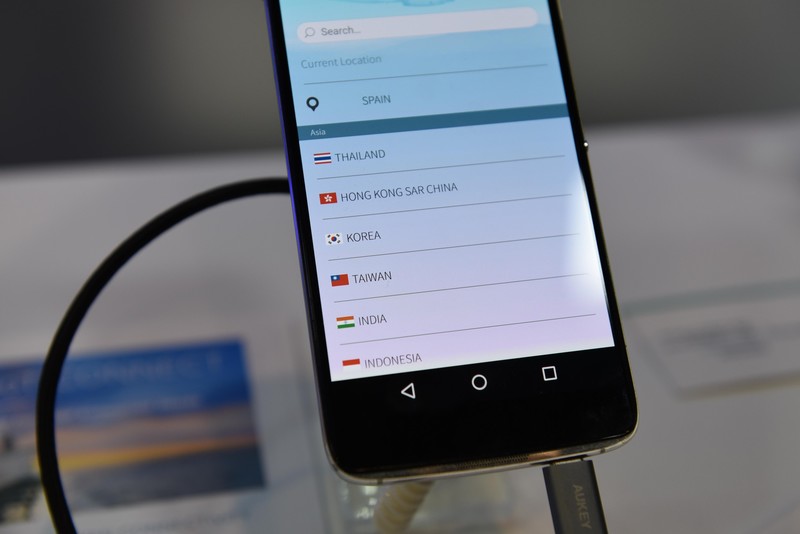

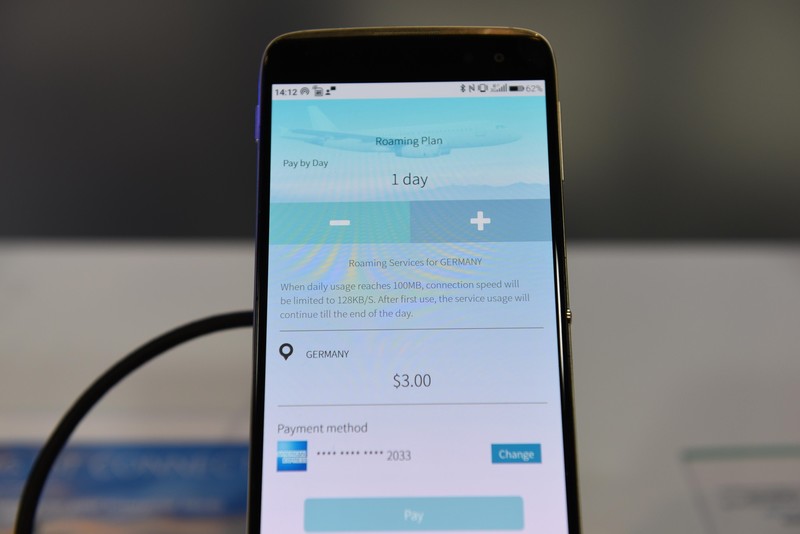

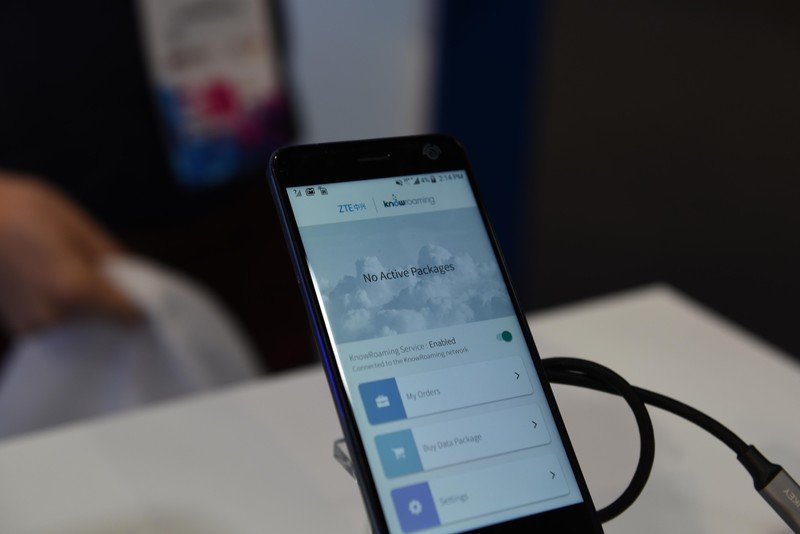

Companies like KnowRoaming, a Toronto-based startup, are bypassing the carriers entirely by working with phone manufacturers like ZTE and Alcatel to integrate so-called Soft SIMs into their handsets. Built directly into the phones themselves, the goal is to allow owners of those devices to connect to any network anywhere in the world on an as-needed basis. KnowRoaming, which began its life as a provider of ultra-thin SIM stickers that performed the same function as its Soft SIM, works with carriers around the world to lock down cheap rates for a la carte data. 100MB in Spain, for instance, costs just $3 USD per day. And while service is currently limited to 3G, things will get much more interesting when LTE service is enabled later in 2017.

Soft SIMs are different from eSIMs in that they are built into the phone's baseband chip and controlled mainly by software that taps into an app, and a constantly-updating pool of international network providers. eSIMs are a little less flexible; they are the manifestation of a physical SIM card but built into the phone, often working alongside a primary SIM card to facilitate roaming, and often have ties to specific carriers. The most famous example is the eSIM card built into Apple's iPad Pro, which allows users to connect to a number of Apple partner networks throughout the world, though, like all handsets, there is a primary unlocked SIM slot for a single carrier.

Right now, these solutions are more curiosities than must-haves, but that may change as more manufacturers get involved.

Soft SIMs and eSIMs fulfil largely the same purpose: providing virtualization to a primarily analog, physical interface. It's better for the consumer to be able to pick the network he or she needs on an a la carte basis. Some companies, like Otono sub-brand Always On Wireless, provides access to dozens of networks around the world in as little as one-hour increments. Though more expensive in aggregate, the idea is to provide as many options — and as much choice — as possible to the average roamer.

Such solutions were common at Mobile World Congress this year, purporting to show the future of mobile connectivity in the wake of phones that, through baseband manufacturers like Qualcomm, Intel and MediaTek, can connect to almost every network in the world. Right now, these solutions are more curiosities than must-haves, but that may change as more manufacturers get involved — though the virtuous (for them) cycle of carrier and phone maker isn't likely to be disrupted any time soon, as long as companies like Samsung and Apple sell the majority of their phones through those familiar sales channels.

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

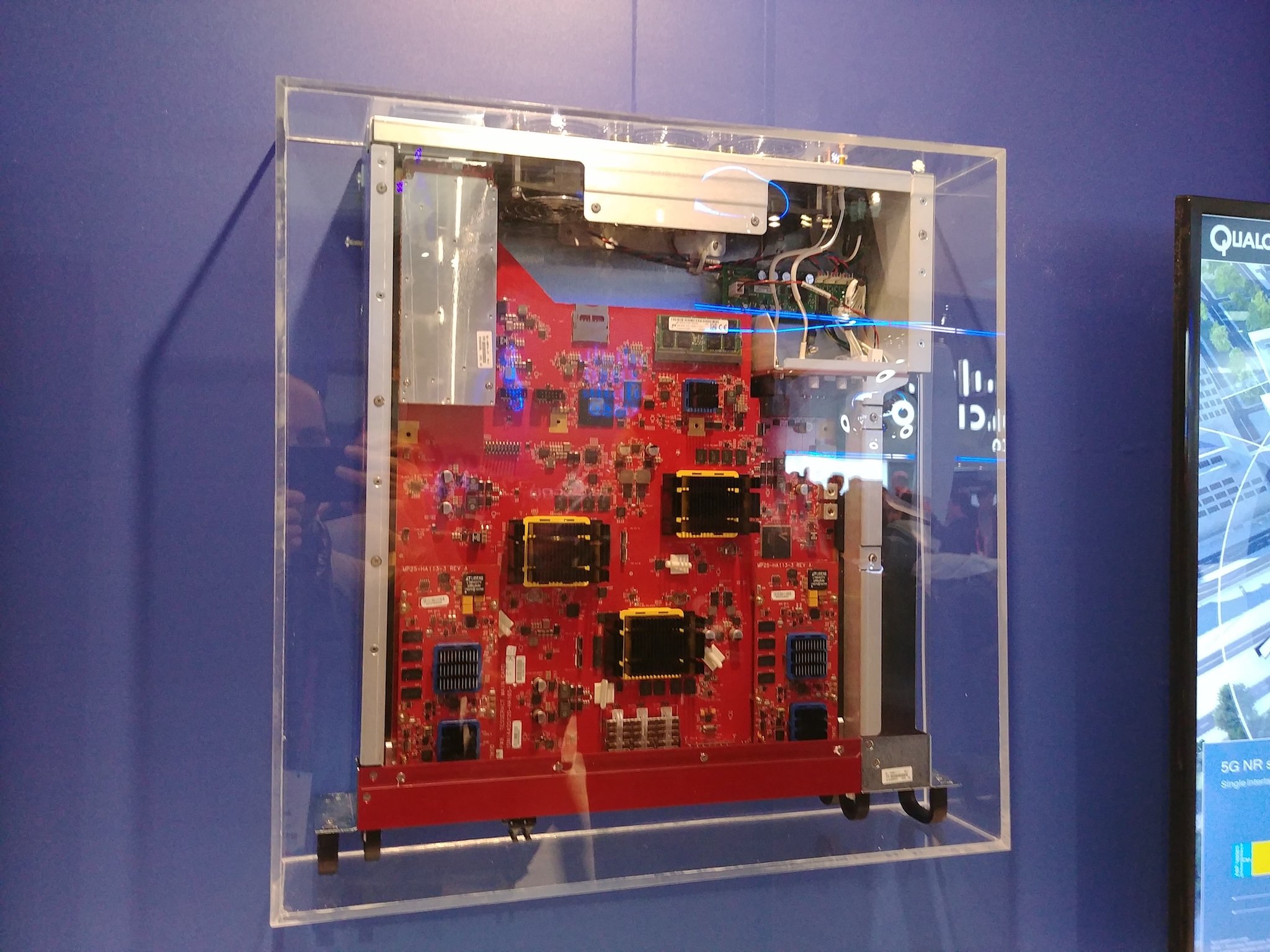

Speaking of Qualcomm, the company showed off two significant products at MWC: a pre-5G Gigabit LTE solution that's shipping with the Snapdragon 835; and a longer-term 5G modem that, right now the size of a desktop computer, will fit inside a regular-sized phone by 2019. The run-up to 5G has a lot of people wondering exactly what that will look like.

5G is in a weird transitional phase right now, but the building blocks are there.

As it stands right now, 5G has few definable characteristics, though there are elements that all parties agree on to some extent: that it will comprise mid-to-high level spectrum (4-6GHz at the lowest) and millimeter band, 29-40GHz at the highest, both of which pose some significant problems for mobility. To alleviate that initial crossover strain, Qualcomm has developed solutions, most recently as part of its X16 baseband solution shipping in the Snapdragon 835, that attempts to increase capacity for everyone on the network.

Because the technology utilizing gigabit LTE is inherently more efficient than those at lower speeds — a highway of cars going 200km/h is better utilized than one where everyone is limping at 80km/h — Qualcomm wants it to proliferate as quickly as possible, since the more people connecting at higher speeds makes the entire network run better.

But Gigabit LTE uses existing technologies, just maxed out and taken to their logical next steps. 5G is something much different, taking advantage of small network cells installed not on rooftops but in street lights, and implemented in roving bands of autonomous robots supplying extremely wide network capacity where it's needed. Think of AT&T or Verizon being able to deploy an entire city's worth of wireless spectrum at the Super Bowl at a fraction of the cost of rolling out permanent towers with equipment that can be moved to a different area the following day. It's a dream that many network operators have been dreaming about for 20 years.

These dreams are what makes Mobile World Congress, after the hubbub of the phone launches and frantically running around the city. The next big idea in mobile is both an tantalizing dream and just around the corner, waiting for the right circumstance, and the necessary deals, to make it happen.

All the phones we touched at Mobile World Congress

Daniel Bader was a former Android Central Editor-in-Chief and Executive Editor for iMore and Windows Central.