Is the world really ready for an Amazon wearable for kids?

About a month and a half ago, Bloomberg reported that Amazon had apparently been working on a wearable device aimed at kids ages 4-12. The device, allegedly codenamed "Seeker," would cost $99 and was rumored to feature built-in GPS to help parents keep track of their children, Alexa voice access to allow kids to message their parents, and access to curated Amazon Kids+ content (with a $2.99/month subscription). Android Central reached out to Amazon for more information of the report, but the company declined to comment at this time.

Amazon was supposedly exploring the possibility of adding the Seeker device to its 2020 product lineup, but it has yet to see the light of day, and perhaps it never will. However, over the past year, Amazon has been actively working on expanding its wearable offerings, including the second-generation Echo Frames and Echo Buds, as well as its Halo fitness wearable and service.

Among the major differences between those devices and the Seeker is that those are intended for use by teenagers and adults, and they all require a smartphone to maintain a data connection. In contrast, the Seeker band is intended for children and would be able to operate with its own cellular, GPS, and perhaps other IoT connections.

But what if Amazon did release the Seeker, or what if it still plans to? How would such a device be received in the current climate? What are the privacy implications of such a device? I have my own concerns about kids trackers, but my own children are well beyond the age range targeted by this device. So I decided to reach out to some of my colleagues who have younger siblings, children, and grandchildren to see what they thought about the idea. I also got some feedback from some of the smartest wearables analysts in the business.

Here is what they had to say about the idea of an always-connected wearable tracker for kids from Amazon.

Cautiously optimistic

When I first brought up the topic of Seeker with my team, I was prepared to hear all about what a terrible idea it was and how Amazon was the last company that parents should trust their kids' private information to. The initial reactions I got, however, were much more positive than I'd expected.

Derrek Lee, Android Central (AC) news team lead, immediately perked up when he heard about the Seeker and told me that this was exactly the type of device that he could envision giving to his younger brother, who is under 12 and not quite ready for the responsibility, or expense, of a smartphone.

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

I also heard from Chris Wedel, one of AC's first-rate freelance writers. Wedel has tested dozens of kids trackers, smartwatches, and connected gadgets with the help of his two young boys, and as you might imagine, he has a lot to say on this topic.

"The idea of putting a device on your child that can be used to track, communicate with, and encourage them is a dicey prospect..." but "as a parent of two young boys and someone knees deep in the consumer tech world, I still have chosen to allow my oldest son to wear such a product."

Wedel lives in a rural community where it's not exactly easy or convenient to know where his kids are at all times. "The ability to locate my son when he is at school, after school to make sure he's gotten onto the bus, and talk to him when needed are just a few of the benefits we enjoy with a connected smartwatch."

Many have criticized Amazon's hunger for customer data, but Wedel is optimistic that Amazon can and will do the right thing here. "Amazon already has a great start in kids' tech. It can bring a lot more focus and resources to an underserved segment."

Indeed, Amazon was one of the first tech companies to provide robust parental controls and age-appropriate content on its Kindles, Fire tablets, and Echo devices aimed at younger children with its Freetime (now Kids+). "Leveraging its expertise in the software space and applying that to a wearable would allow parents to feel more comfortable using such a product because it is from a provider who has already earned their trust," says Wedel.

Carolina Milanesi, president and principal analyst at Creative Strategies, also isn't particularly concerned with the idea of a company like Amazon controlling this kind of technology. "Transparency is what I would want as a parent. I am not sure the concerns are different whether it is Amazon or Apple that my kid is wearing."

People from all walks of life on different devices and operating systems regularly rely on Amazon devices, apps, and services.

Another reason that such a device could be successful is that Amazon operates quite nicely across various tech cross-platforms. Its apps and devices work on Android, iOS, and Windows and are used by those in multi-device households. "Amazon is used by people from all walks of tech-life," says Wedel. A device like Seeker would surely be compatible with both Android and iOS phone users, allowing for a more expansive tracking network than a more siloed ecosystem might.

And because of its scale and the fact that it's willing to sell devices at or below cost, Amazon can also afford to price a device like the Seeker at a point where more families could afford it. According to the Bloomberg report, the Seeker would be priced at $99, with an optional $2.99/month Amazon Kids+ subscription. This puts it $100 under the comparably-spec'd TickTalk 4 connected kids smartwatch, though priced slightly higher than kids fitness trackers (without GPS or connectivity) like the Fitbit Ace 3 or Garmin Vivofit Jr 3.

You could just use something like an AirTag or Tile tracker, but you'd be missing out on a ton of useful functionality.

There are cheaper tracking options such as Apple's AirTags or Tile trackers, but those don't have the extended functionality of a wearable like Seeker. Jitesh Ubrani, research manager at IDC who specializes in mobile device trackers, told me that "if a parent simply wants to track their child's location, then AirTags would be a great alternative. However, if parents truly want an emergency contact device for their child which can work across multiple location tracking technologies (e.g., cellular, GPS, Bluetooth), Amazon's Seeker would be ideal, and Amazon stands a good chance at displacing companies like Verizon."

Pragmatically suspicious

The first potential issue that comes to mind when discussing a wearable that tracks the location of a minor is the potential for data leaks, breaches, or nefarious targeting, and what might happen to your child's data, or your child, if that were to happen.

The worst-case scenario, obviously, is "some hacker getting to know the whereabouts of your child," says Nishanth Sastry, professor of computer science at the University of Surrey in the U.K. "A less obvious one could be that it might give parents a false sense of security," Sastry explains. For example, "a kid might leave their tracker behind at home and slip out of the house. Or a kidnapper might get someone else to take the device to the school, and the parent might think the kid is safe because of the location of the device." Granted, these potential risks are extreme and not at all limited to the Seeker, but they're worth considering if a parent is thinking about giving their kid an always-connected tracker.

What might be even more frightening than the palpable risks like nefarious actors in the chain or data breaches are those risks that we haven't yet foreseen. First and foremost among these is the question of just what Amazon (or any company) will do with location and tracking data in the future (just look at the stories coming out of Kabul where the Taliban have allegedly taken possession of biometric data left behind by the U.S. armed forces). Granted, that's an extreme scenario, but it just goes to show how things can spiral out of control and beyond what anyone may have anticipated.

As my colleague and AC senior editor Jerry Hildenbrand points out, that uncertain future is worrisome, particularly when it comes to children. "Amazon, like Google and Facebook, is really good at harvesting our data," Hildenbrand says. "We don't think about Amazon being a data company, but it's really good at converting the things it knows about you into ads. So things that seem inconsequential to you or me, like how many times we went out for lunch this month, are opportunities to make money for companies that collect and compile data."

"I'm more worried about what Amazon will do with it in the future," Hildenbrand says. "The data collected about us is never really deleted, and I just don't think Amazon has any business starting its data portfolio so early in life."

The data collected on us is never really deleted and will likely follow us around our entire lives.

Sastry concurs and warns about the danger of "Amazon starting to accumulate data about little children and potentially track them into adulthood. The degree of centralization and knowledge about individuals should worry the children more" than the parents says Sastry because large corporations will be able to predict (and dictate) behavioral patterns into young adulthood and beyond with little or no say from those affected — the children being tracked.

Sastry told me that he would not equip his own kids with a device like the Seeker. However, he did say that as a parent considering such a device, he "would also want to know how exactly the data was being used" and that companies like Amazon should offer mechanisms "to obtain parental consent before deploying machine learning models that are trained based on this data."

Wedel, who, as we mentioned before is bullish on the idea of Seeker, was also optimistic about the idea of Amazon integrating such a tracker with its other connected IoT platforms. For example, he says that "an Amazon wearable could also be nicely integrated with other services such as Ring. With the Neighbors app, it's opt-in, so if something happened and their child wasn't home yet or went missing, it could ping the network for help or alert the police. If activated by the parent, it could possibly start using the Ring network or even using Amazon Sidewalk for help to better pinpoint where the child is and has been."

This situation presents a potential nightmare scenario for many privacy pundits, even though, to give Amazon credit where it is due, many of those same privacy advocates who've been critical of Amazon's policies and ambitions in the past were quick to point out that the company seems to have taken the right steps to protect users of the Sidewalk network.

Amazon has been very careful with its Sidewalk rollout, but that doesn't mean there isn't the potential for it to be exploited in the future.

Still, analysts like Milanesi don't think that Amazon would be quick to integrate a kids tracker with its larger IoT platforms like Sidewalk or Ring. "I am not sure it would be a good idea for now. I am sure Amazon will be very careful here."

And Sastry was cautious to point out that while "any connection through Sidewalk is likely to be encrypted," that shouldn't give parents a false sense of security. "The very fact that a device is connected could leak information — e.g., a creepy neighbor could track if a child regularly comes near their house on the way to school." However, such dangers are more easily mitigated the larger the user base is because it provides greater anonymity.

However, Sastry was decidedly not on board with Wedel's suggestion to have the Seeker device connected to Amazon's Ring network and Neighbors app to help track down missing or lost children. "This would be a massive violation of privacy if every child's image (whether missing or not) from a Ring camera was to be passed on to law enforcement."

Sastry also brought up the inequality card here, pointing out that it's likely that "only children in rich neighborhoods with Ring cameras being identified and children in poorer neighborhoods not getting any benefit. Yet, similar to Apple's recent CSAM scenario, it may be too powerful a tool for too little expected gain in the end."

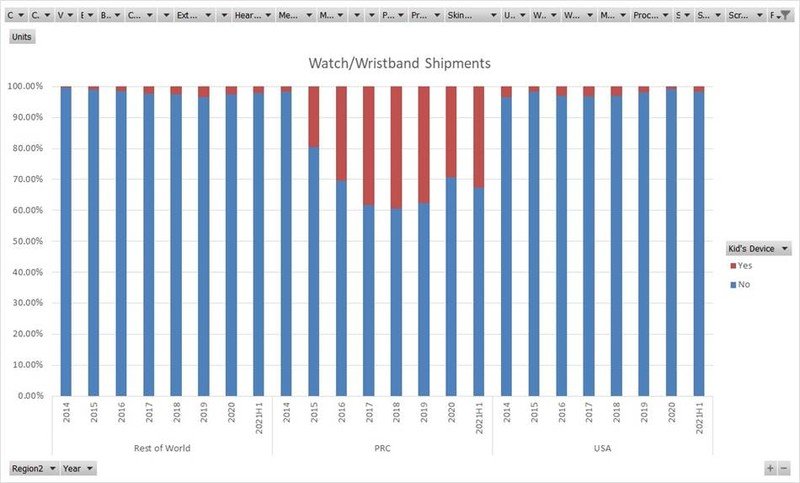

And what about the potential commercial success of the Seeker? Regardless of data privacy or safety concerns, is there even a market for such a device? The data seems to indicate that America isn't quite ready.

IDC analyst Ubrani did concede that "Amazon's offering would be more attractively priced than other brands that offer something similar including location tracking." However, attractive prices don't guarantee massive sales. "The real question is how many parents actually want the emergency type of device? I, for one, don't believe that's a very large or lucrative market in the US."

Ubrani says that companies in the U.S. have been trying to generate demand for kids-focused trackers for years. While there have been some upticks in sales like when Garmin or Fitbit introduces a new or refreshed device, the "kids wearable market has always floundered in the U.S."

The reason that such devices are more popular in a place like China has more to do with its former "one-child policy, as well as a big push from telcos," Says Ubrani, but that those factors just don't exist in other parts of the world. "Many parents either give their kids a phone or an older wearable which further negates the need for a dedicated kids wearable."

Based on this data and background knowledge, Ubrani concludes that there probably isn't a very lucrative market for kids-focused wearables in the U.S.

Lojack, and Jill

Data privacy and location tracking are sensitive topics, but particularly so when it comes to minors. It could be that Amazon weighed the issues raised above (and more) and concluded that it wasn't the right time to bring something like Seeker to market. Alternatively, it could be working on bolstering its policies and protocols to address these and other concerns before it considers launching such a device. Regardless of what it or other tech companies decide to do in this space, it's important that parents and regulators ask the right questions before they consider using tracking technology with their young children.

What do you think about the idea of an always-connected kids tracker? Does it matter if the manufacturer is Amazon or another big company? Share your thoughts in the comment section.

Jeramy was the Editor-in-Chief of Android Central. He is proud to help *Keep Austin Weird* and loves hiking in the hill country of central Texas with a breakfast taco in each hand.