Allo Messenger is a big deal for Google's mobile-first strategy

In recent years, Google has released no fewer than eight ways to communicate with friends and family. From the heady, Jabber-powered simplicity of Google Talk to the bulging interior of Google+ Messenger to the most recent volley, Hangouts, to say Google has struggled to capture market share in the effervescent messaging space is an understatement.

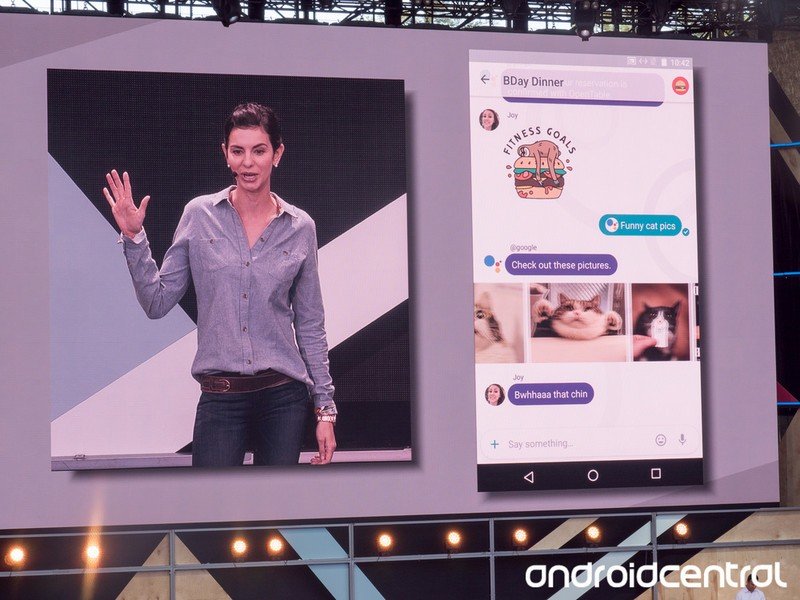

These days, Talk is no more, and Google+ Messenger was rolled into Hangouts in 2013. With the announcement of Allo, Google's newest artificial intelligence-powered chat app, it would seem that the company struggling to connect with with consumers in this increasingly-lucrative space is once again poised to be outplayed by the incumbents, names like WhatsApp and Line and WeChat.

Indeed, Google's tenacity in returning to messaging is remarkable given its poor track record. Allo, even with a sufficient tally of unique features, appears to be little more than a showcase for the Google Assistant, a confluence of research into artificial intelligence and machine learning that coalesces into a bot available to the user at any time.

Minimizing Allo's potential impact on the market is shortsighted given Google's newfound approach to app development.

But minimizing Allo's potential impact on the market is shortsighted given Google's newfound approach to app development. Not only was it announced alongside an ultra-simple but technologically advanced video app, Duo, but Allo is proudly mobile-only — Android and iOS, specifically — and uses a customer's phone number for authentication. In that way, it picks up some of what makes WhatsApp so compelling, along with pieces from others like Facebook Messenger (bots), Telegram (Incognito Mode), Signal (end-to-end encryption), and Snapchat (doodles, timed messages).

Breaking down those individual components, it's plain why Google built Allo, keeping it separate from Hangouts. First, the app doesn't require a Google account, which cleans the slate for mobile users who still have a metallic taste in their mouths from the forced linking of Google+ to other services on the company's platform. While users will benefit from pairing their Google accounts with Allo, by giving the bot more context about their likes and dislikes (and their previous searches), the linking the two is neither necessary nor intrinsic to getting use from the assistant.

Relying on a phone number for authentication over a Google account further restricts and focuses the app: a single point of entry, and no desktop mode. Unlike Hangouts, which subsumed Talk, which was built into Gmail on the web, Allo will always be mobile-first, a hugely important tenet of the success of both WhatsApp and Instagram — both owned by Google competitor Facebook — along with Snapchat, the ultimate mobile-only messenger. (Yes, WhatsApp has since grown to have desktop apps, but they are still directly linked to a single-instance mobile device. You can't sign up for WhatsApp from the web.)

Allo gives Google a way to experiment with features without worrying about reaching parity on the web.

This unbundling of Google's primary messaging platform allows Allo to scale across mobile in ways that Hangouts never could. It also gives Google a way to experiment with features without worrying about reaching parity on the web, a rising tension among messaging startups. Google, unlike many of its competitors, has leeway to make these decisions, given its existing product lineup. Don't want to use Allo? Hangouts isn't going anywhere.

Be an expert in 5 minutes

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

It's also no accident that Allo is the Google assistant's first host: a messenger app allows the company to be nimble and imperfect, allowing the tool to grow within its confines, rather than represent the bulk of the opportunity, like Google Home, the company's speaker-cum-voice-companion. Google Assistant is at the heart of what the company hopes is its next salvo in continuing to dominate search, which is inevitably turning into something more contextual and mobile. It's one thing for Google's in-app bot to be able to identify clams in a photo of a bowl of seafood linguine; it's another to use that information to make it useful in helping people make better decisions about where to eat, how to get there, and how to pay for it.

Of course, no number of features and amount of finesse will guarantee Google a place at the messaging table, increasingly dominated by Facebook and Snapchat in the West, and Line and WeChat in the East. But Google has to try, and in trying has to set itself up to iterate quickly should it fail. None of its previous messaging concerns have been mobile enough, in the canonical sense, to properly compete with the incumbents, and there is good chance Allo is too late to the game to make an impact. But whereas Facebook's past messaging app failures — who remembers Poke, or Slingshot?— have long been forgiven as they're forgotten, people tend to hold onto Google's duds, because they feel almost like betrayals.

The truth is that Allo may very well be inconsequential, a blip on Google's, and our, radar in its grand platform strategy. But its core tenets — data-gathering, bots, and a mobile-first approach — will not be. Those unequivocally represent Google's future, and will impact as many people as use the internet today. It is in this context that Allo should be viewed, not as a short-term mistake, but as a long-term bet on mobile.

More: Unified messaging is a joke, and it probably always will be

Daniel Bader was a former Android Central Editor-in-Chief and Executive Editor for iMore and Windows Central.